-- Published: Wednesday, 21 November 2018 | Print | Disqus

A recent MarketWatch article notes that:

GE was one of Wall Street’s major share buyback operators between 2015 and 2017; it repurchased $40 billion of shares at prices between $20 and $32. The share price is now $8.60, so the company has liquidated between $23 billion and $29 billion of its shareholders’ money on this utterly futile activity alone. Since the highest net income recorded by the company during those years was $8.8 billion in 2016, with 2015 and 2017 recording a loss, it has managed to lose more on its share repurchases during those three years than it made in operations, by a substantial margin.

Even more important, GE has now left itself with minus $48 billion in tangible net worth at Sept. 30, with actual genuine tangible debt of close to $100 billion. As the new CEO Larry Culp told CNBC last Monday: “We have no higher priority right now than bringing those leverage levels down.” The following day, GE announced the sale of 15% of its oil services arm Baker Hughes, for a round $4 billion.

Of course, since that sale values Baker Hughes at $26 billion, and GE paid $32 billion for 62% of Baker Hughes as recently as last year, which looks to me like a valuation for the whole company of $52 billion, GE shareholders appears to have lost half the value of their investment in Baker Hughes in about 18 months.

But GE is just one of several hundred big companies with CEOs who now have to justify a massive, in some cases catastrophic waste of shareholder cash.

This most recent share buyback binge was dumb money on steroids, with artificially low interest rates leading corporations to borrow big and buy back their stock on the twin assumptions that 1) since the cost to borrow was less than their stock dividend, they were generating “free cash flow” and 2) buying their own stock forced up the price, which would make the CEO look smart.

Both assumptions were only valid while the market was rising. And since most of the buying took place late in a bull market, with share prices at or near record highs, it was only a matter of time before a correction or (more recently) an actual bear market turned that free cash flow into a monumental capital loss and made that smart CEO look not just dumb but criminally negligent.

The examples of corporate dumb money in action are many and varied, but a few are up there with GE in terms of egg-on-the CEO’s face, chaos at the annual shareholders meeting entertainment value. Big Tech icons Apple, Alphabet, Cisco, Microsoft and Oracle, for instance, repurchased $115 billion of stock in the first three quarters of 2018, while devoting only $42 billion to capital spending.

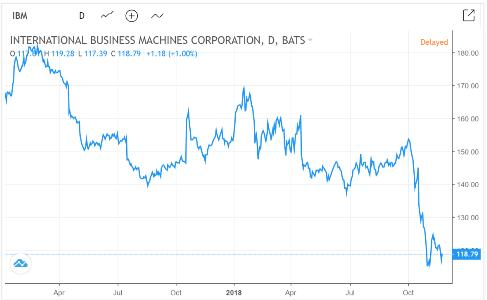

IBM is an even better story. It bought back $50 billion of its stock between 2011 and 2016, cutting its shares outstanding by, well, here’s the chart:

Then, with its stock up (because the falling share total turned declining earnings into growing earnings per share), it just kept on buying. Here’s how the company phrased it in its Q2 earnings press release:

IBM’s free cash flow was $1.9 billion. IBM returned $2.4 billion to shareholders through $1.4 billion in dividends and $1.0 billion in gross share repurchases. At the end of June 2018, IBM had $2.0 billion remaining in the current share repurchase authorization.

IBM ended the second quarter with $11.9 billion of cash on hand. Debt totaled $45.5 billion, including Global Financing debt of $31.1 billion. The balance sheet remains strong and is well positioned for the long term. [Emphasis added]

Then this happened (did I mention that this late in the cycle a bear market is inevitable?):

Now much of the cash that the company “returned” to shareholders has become money that the company lost for shareholders. And – here’s where the macro part of the dumb money story begins – the fact that corporate America has leveraged itself to the hilt to buy back stock leaves hundreds of companies in varying degrees of dire financial straits. In other words, with sales growth slowing and free cash flow evaporating, these over-leveraged companies will have to raise capital to shore up their balance sheets. But interest rates are up, which makes new borrowing a massively cash flow negative proposition. Asset sales, meanwhile, become “fire sales” in a downturn (note the above GE example), so that’s a painful and embarrassing option. What’s left? Why, equity sales, of course.

So – as usually happens at the end of long credit parties – the same companies that bought back their shares so aggressively at ever-higher prices now have to pull those same shares out of storage and sell them at ever-lower prices, creating a mini death spiral in which a rising share count pushes down the share price, necessitating more equity sales, and so on.

Each annual proxy vote becomes a referendum on the once-brilliant CEO’s intelligence, and numerous formerly “well-run” companies end up failing. General Motors, you might recall, declared bankruptcy in 2009. And there is actual speculation that GE might be heading that way this time.

| Digg This Article

-- Published: Wednesday, 21 November 2018 | E-Mail | Print | Source: GoldSeek.com