-- Published: Sunday, 21 June 2015 | Print | Disqus

Watch out! That is what the headline said on the cover of the latest edition of The Economist (June 13-19, 2015). The world is not ready for the next recession. The Economist went on to declare “the fight against financial chaos and deflation is won”….the IMF says, for the first time since 2007 every advanced economy will expand…. Growth should exceed 2% for the first time since 2010….and (the Fed) is likely to raise rock-bottom interest rates.”

Well that is the forecast of the IMF. The Economist doesn’t seem to be quite as optimistic as even their 2015 forecast is suggesting GDP growth of 2.3% for the US, 0.8% for Japan, 1.8% for Canada and 1.5% for the Euro zone. That seems a bit shy of 2% for the rich world. At least The Economist admitted there remains risk from the “Greek debt saga” to “China’s shaky markets”. But one of the big problems is that six years following the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression the global economy is at best muddling along while the risks appear to be rising not falling.

Take Greece as an example. There are many who believe that Greece is not much of a problem given that they only represent roughly 2% of the Euro zone economy. On the other hand, there are many who believe that a Greek default could represent a Lehman Brothers moment for the Euro zone. If there is a difference the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 came as a shock to the market while the potential for a Greek default has been “in the headlines” for months. On the other hand, someone, most likely the ECB, the Bundesbank, or the IMF could be left holding worthless Greece debt. It is believed that the EU banks are no longer exposed to Greece. What is unknown is whether the collapse of Greece could spread to other countries (contagion).

Whether Greece stays or leaves the EU or continues to use the Euro should not be a major concern. There are countries who are not EU members but use the Euro (Kosovo, Montenegro and others) and there are countries who are members of the EU but do not use the Euro (United Kingdom, Poland and others). If there are fears concerning Greece, it is the potential for contagion. The entire Euro zone is in need of reform not just Greece. If Greece collapses and leaves the Euro zone the focus could shift to other countries in the Euro zone where the problems with pensions and the social welfare system are not much different. Italy and France are the most mentioned as other potential debt bombs waiting to go off but there are numerous other Euro zone countries that have debt problems as well. The thought of the potential for more sovereign defaults could put further upward pressure on interest rates.

Greece has numerous other problems that go beyond the headlines of the ongoing negotiations with its creditors. There has been considerable social unrest. There have been numerous suicides as people fail to cope with the ongoing crisis. Withdrawals from the banking system have continued at a rapid pace with word that depositors pulled some €2 billion out of the banking system in a matter of 3 days recently. That is double what the ECB recently provided the Greek banks as emergency liquidity assistance (ELA). Capital controls could be next as was seen in Cyprus in 2013. Official unemployment is 25.6% but youth unemployment exceeds 50%. Yet they talk about Greece being only in a recession. Many others believe the evidence suggests they are in a depression.

China has been one of the largest borrowers since the financial crisis of 2008. Chinese debt has soared by upwards of $30 trillion more than quadrupling debt since 2007. The Chinese total debt (government, corporate, household) has soared to around 300% of GDP a level that puts them closer to the US and larger than Germany. Much of the new debt has emanated in China’s overheated real estate market or the unregulated shadow banking system. As well, numerous local governments have issued potentially unsustainable levels of debt.

All of this comes against the background of a slowing Chinese economy. Chinese trade data suggests that China’s growth may be slowing faster than the government wants. As well, the Chinese stock market has soared into what many term as bubble territory as it has drawn in numerous retail traders and other speculators looking to make a quick buck (or is it Yuan). If there is any positive to this massive debt growth in China is that the central bank (PBOC) still has considerable capacity to bail out the economy if it should falter further or if defaults mount. Chinese GDP growth has recently fallen under 7% the lowest level in years.

Debt could become a “dirty” word. China and Greece are in some respects just the tip of the iceberg. Yet oddly, The Economist article appears to pay lip service only to what potentially could become a huge problem. Average debt to GDP ratios have grown sharply since the 2008 financial collapse and are estimated on average to have grown 40%. There are a couple of ways of measuring debt to GDP. The most common is government debt to GDP. According to December 2014 figures government debt to GDP for the G7 countries were as follows: Japan 230%, Italy 132%, USA 102%, France 95%, United Kingdom 89%, Canada 87% and Germany 75%. Anything over 100% takes at least 1-2% off GDP growth.

When one takes into consideration total debt (government, corporate and household), the numbers can be even more astounding. The following is the total debt to GDP (public plus private) for the G7 as of 2013. The levels are most likely higher today: Japan 650%, United Kingdom 550%, US 350%, Canada 300% and the Euro zone 475%. It is estimated today that global debt has grown to $223 trillion from roughly $157 trillion in 2008. The growth rate of debt has far surpassed the growth rate of GDP.

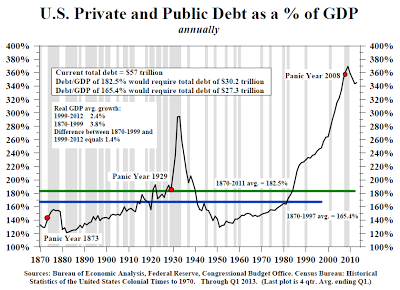

Below is a chart of public and private debt to GDP for the US. Note how sharply it has grown since the depths of around 1950. The chart only goes to Q1 2013. Today total public and private debt to GDP is around 343%. The biggest debt growth for the household since the 2008 financial crisis has been student loans, consumer credit card debt and auto loans (8 year financing for auto loans). And as with the subprime mortgage market that was at the heart of the 2008 financial collapse much of this debt has been securitized and sold off in packages.

Source: www.bls.gov, www.stlouisfed.org, www.cbo.gov, www.census.gov

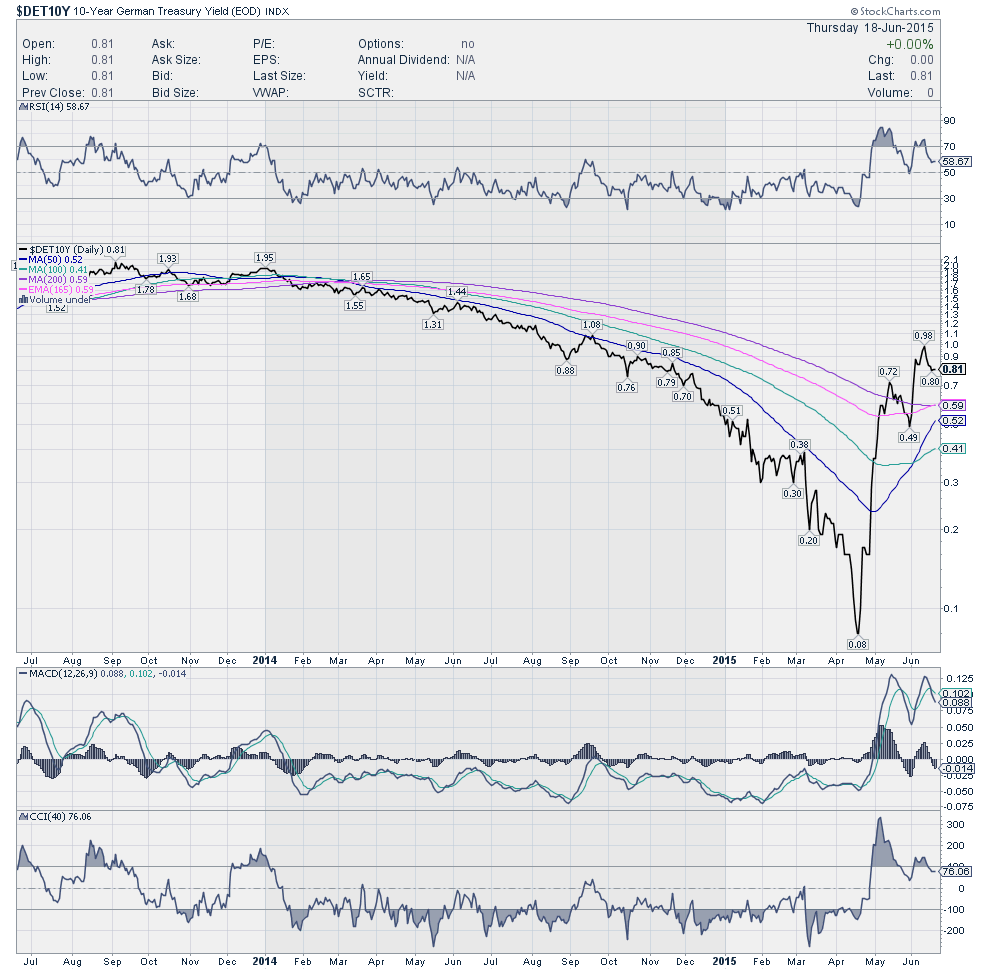

With all the debt maybe it is not surprising that interest rates are rising. It was only a short while ago that in the Euro zone there was roughly $2.5 trillion of debt trading at negative interest rates. With the recent back up in interest rate yields (prices that move inversely to yields fell); there is apparently only about $1 trillion of debt trading at negative interest rates now. German 10 year bund rates rose by a factor of 10 from roughly 0.08% to over 0.80% since April 2015. On that basis, it would put bund buyers who purchased securities over the past year underwater. It is unknown as to what losses might have occurred given the rapid back up in yields.

Interest rate rises have not been exclusive to the Euro zone. All developed countries have experienced a rise in interest rates mostly at the longer end of the yield curve. All the talk has been about the Fed hiking interest rates. The bond market appears to be doing it for them. Only the Fed doesn’t control the long end of the yield curve as they do with the short end of the curve. The trouble with a rise in interest rates at the long end of the yield curve is that it has a negative impact on a host of loans particularly the mortgage market.

Evidence has suggested that as a result of concerns about the bond market that dealer inventories have been falling, dealers have become more reluctant to make a market for product particularly for corporate bonds, and overall volumes have fallen. Evidence also suggests that bond funds and others have increased their holdings considerably during the market rally in yields that took place between 2013 and 2015.

Source: www.stockcharts.com

The chart of the 10-year German bund shows that the rapid interest rate rise since April has wiped out all of the gains since at least November 2014.

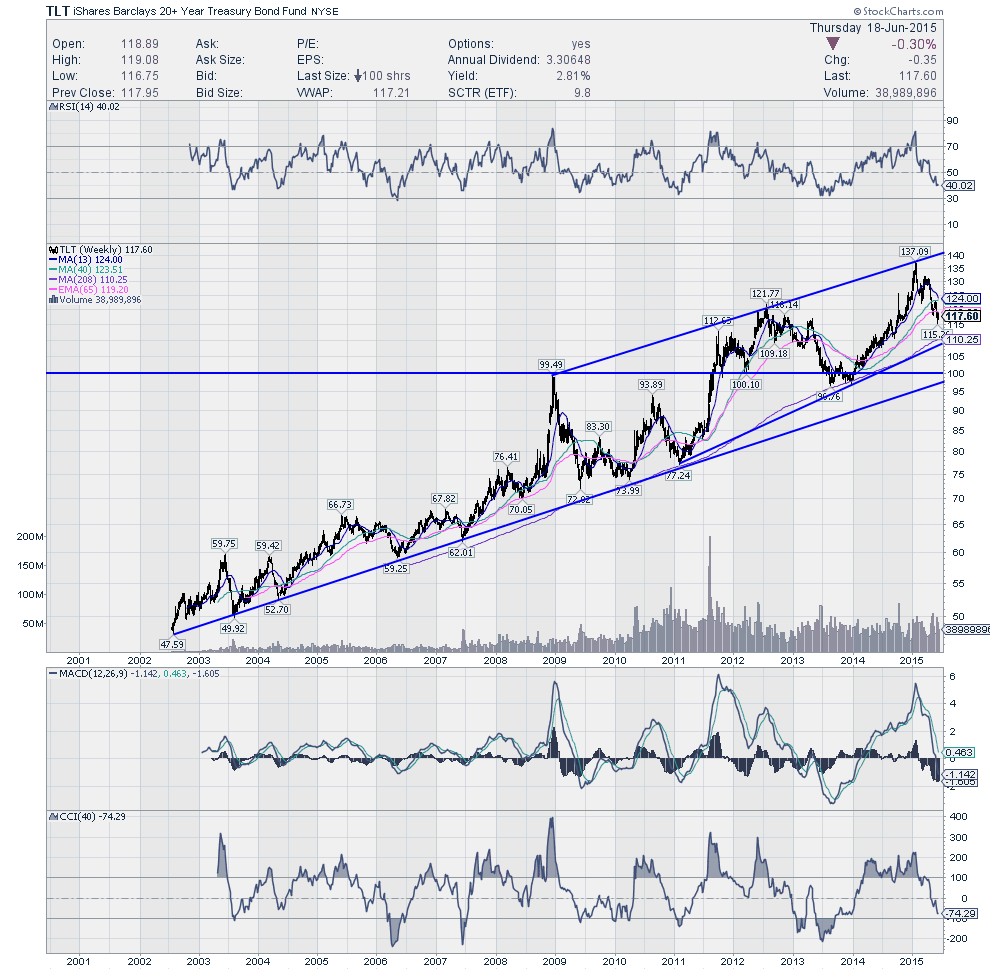

Source: www.stockcharts.com

The longer dated chart of the iShares Barclays 20+ year Treasury bond fund (TLT-NYSE) shows they have fallen $20 since late January 2015. Major support does not come in until down around 100. Major bond market lows have been seen roughly every 6/7 years since the major low in 1981. Major bond lows were seen in 1987, 1994, 2000 and 2006/2007. There was, however, also a major bond sell-off in 1984. Counting from that low using the same 6/7 year cycle there were visible bond lows in 1990, 1997, 2004 and 2010. If that cycle is being followed then a major bond low could be seen in 2016.

Major declines in bond markets have in the past been accompanied by considerable market turmoil. Bond yields were pushed down by overblown expectations for the QE program of the European Central Bank (ECB) and the ongoing QE program of the Bank of Japan (BOJ). The Federal Reserve’s QE program came to an end in October 2014. But expectations in particular from the ECB QE program helped push yields down to new lows (prices to new highs). Now oversupply and growing credit concern has reversed much of the decline in yields quickly. This has a potential negative impact not only for bond speculators but a host of funds and pension funds. Of larger concern is the $700 trillion derivatives market. Interest rate swaps (IRS) dominate that market. In addition Credit Default Swaps (CDS) could also become a problem as was seen during the 2008 financial crisis that brought the giant insurance company AIG close to bankruptcy. Liquidity has suddenly become a concern as buyers dry up and regulatory changes (capital requirements) at the major banks may also be impacting the capability of the major financial institutions to participate in the bond markets.

Bond funds have grown sharply since the 2008 financial crisis pushed by low interest rates and an endless stream of supply. And it has not just been concerns over sovereign debt that has helped push yields back up. The collapse in oil prices has left upwards of $5 trillion worth of oil debt vulnerable. Much of this debt was borrowed at low rates when oil prices were high. This is not to suggest that all this debt is vulnerable but that some portion of it may be vulnerable. Of larger concern might be upwards of $14 trillion of emerging market debt much of it issued in US$. The US$ has gone up sharply since July 2014 with the US$ Index going from 80 to 100. The opposite side of a sharply rising US$ is other currencies have been falling. The result is the US$ debt has become considerably more expensive for those foreign borrowers. Already there have been defaults but it has not yet become major problem.

But if concern over sovereign defaults and other defaults grow there could be a further rush into US$, which would put further pressure on the mountain of US$ debt issued by emerging markets. Finally all the talk of a Fed rate hike has not helped. If the Fed were to hike interest rates in September (and again in December) as many seem to be speculating that could in turn put further upward pressure on the US$ and in turn further pressure on the mountain of US$ debt.

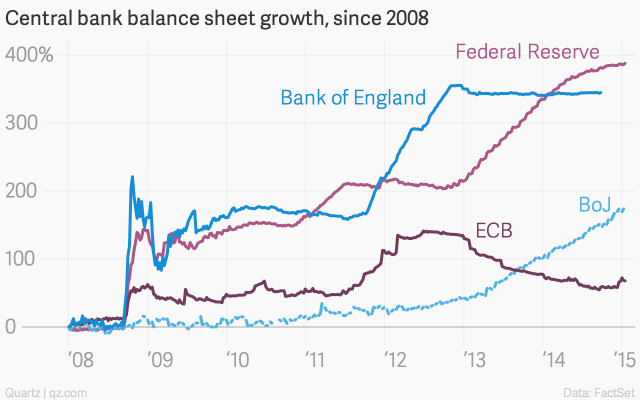

The problem for the central banks is that their ability to respond to another financial crisis and recession has been severely compromised. Central bank balance sheets have experienced explosive growth since the 2008 financial crisis as the chart below attests.

Source: www.qz.com

The key central bank is the Federal Reserve. The Fed has seen its balance sheet explode to $4.5 trillion including $1.7 trillion of mortgage-backed securities of potentially questionable quality. The monetary base has exploded to $3.9 trillion from $875 billion just prior to the financial crisis of 2008. Much of the monetary base is reserves being held for the money centre banks. The monetary base is defined as currency in circulation and reserve balances (deposits held by banks and other depository institutions in their accounts with the Federal Reserve).

No wonder the EU, the USA, Canada and Japan have moved from bailouts to bail-ins in the event of another financial crisis. Bail-ins mean that bond holders and depositors are at risk in the event of another round of bank failures on the scale of what happened in 2008. Traditional methods of fighting a recession have been compromised. With interest rates already at zero or close to it in many of the G7 countries, it is difficult to lower interest rates further. The Fed rate has been at 0-0.25% (mostly 0%) since 2009. No wonder the Fed wants to hike rates so they have room to lower them later. While many are speculating that the Fed will hike in September and even again in December neither is a given. For now, the market is happy that the Fed did not hike interest rates in June.

Greece, China and the bond market are real risks. Yet the stock market continues to trade at or near its record highs. Volatility as measured by the VIX is at or near record lows. Many continue to believe that no matter what, the Fed will “ride to the rescue” in the event of another crisis. As noted, that is not a given.

There is also an overlooked risk. The recent cyber-attack on the Government of Canada’s computers highlights the risks of the potential for an attack on the global financial system. The ongoing tensions in the Ukraine and the South China Seas highlights the growing military tensions that exist today. While many believe the odds of a military clash are low there are many who also believe the odds of cyber warfare is high. This is a consideration that many are overlooking yet the capability of conducting cyber warfare exists with China, Russia, the US, the EU and Japan and others. While cyber warfare works both ways, the thought of major disruptions in the global financial markets could cause considerable chaos.

No wonder there are thoughts that the end game may be in play as tensions play out on the world’s stage.

david@davidchapman.com

dchapman@iagto.ca

www.davidchapman.com