“If this were a marriage, the lawyers would be circling.”

The Economist, My Big Fat Greek Divorce, 6/20/2015

Greece is again all the buzz in the media and on the commentary circuit. If you’re like me, you are suffering terminal Greece fatigue. You just want Greece and its creditors to “do something already” rather than continually coming to the end of every week with no resolution, amid finger-pointing and dire warnings from all sides about the End of All Things Europe – maybe even the world.

That frustration is a common human emotion. Perhaps the best and funniest illustration (trust me, it is worth a few minutes’ digression) is the story about one of my first investment mentors, Gary North, who was working in his early days for Howard Ruff in Howard’s phone call center before Gary began writing his newsletters and books. (Yes, I know I am dating myself, as this was the late ’70s and early ’80s, just as I was getting introduced to the investment publishing business. And for the record, I knew almost everyone in the publishing business in the ’80s. It was a very small group, and we got together regularly.)

Howard set up a phone bank where his subscribers could call in and ask questions about their investments and personal lives. One little lady had the misfortune to get Dr. Gary North on the line. (Gary was the economist for Congressman Ron Paul and went on to write it some 61-odd books, 13,000 articles, and more – all typed with one finger. He is a human word-processing machine.)

This sweet lady lived way out in the country and was getting older. She asked Gary if he thought it would be a wise idea for her to move into the city (I believe it was San Francisco) to live with her daughter. Not knowing the answer, Gary helped her work out the pros and cons over the phone, and she decided to move. A few days later she called back and said that she couldn’t bring her dog with her because of the rules at her daughter’s apartment. It turns out she couldn’t live without her dog, so Gary helped her come to the conclusion that she could stay in the country.

A few days later she called him back asking whether she should change her mind, and Gary once again help her to come to a conclusion. This went on for several weeks, back and forth, move or not move, dog or no dog. Finally she called one last time. Gary, in utter exasperation and not being infinitely tolerant of indecisive people, said, “Look lady, just shoot the dog and sell the farm.” (For the record, I hope she didn't really shoot the dog. I like dogs.)

That is where most of us are with the Europeans and Greeks. I have devoted a great deal of space in this letter to Greece over the past five years and have visited the country and corresponded with many analysts and citizens about the situation. And while I want to briefly outline the Greek situation again today, as there are some subtle nuances to consider, I think this juncture is a teaching moment about the larger picture in Europe. In fact, watching this process, I have come to change my mind about the timing of what I see is the endgame for Europe and European sovereign debt. I think exploring that issue will make for an interesting letter.

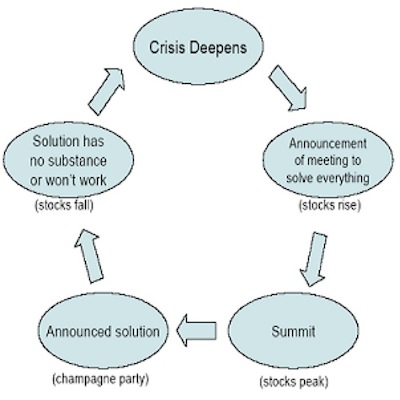

Economic crises go through cycles. Here’s a chart from the clever folks at Valuewalk.com (via my friend Jonathan Tepper on Twitter).

https://twitter.com/valuewalk/status/612948290267688960

The Greek situation is presently caught in those two bubbles on the bottom. European leaders held summit meetings this week to consider new breakthrough concessions offered by Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras. Let the champagne flow. Except those concessions were rejected, and the Greeks rejected the counteroffer as of this afternoon. But it’s not quite midnight yet.

Unfortunately, the wheel of debt never stops turning. If this solution is like countless others floated in the last five years, we will soon learn that it has no substance or simply won’t work. We will then reenter the crisis phase.

Every cycle breaks eventually. If you forget everything that’s happened to this point and re-imagine the crisis as an economic standoff between Greece and Germany, you have to say Germany will win. It outweighs tiny Greece in every possible category. The real question is why Germany let the fight go on this long. We will deal with that in a minute.

Note that this observation isn’t about which country should win; it is about who will win. Greece has some legitimate grievances. Unfortunately, these grievances aren’t going to matter in the end.

Poster Children for European Profligacy

My friend David Zervos of Jefferies & Co. has no doubt who will win. He sent me this note on June 17.

The bell is tolling for Alexis [Tsipras]. European leaders from all sides have abandoned him as he burns through every last bridge that was once in place. His only meeting of importance during this crucial week of negotiation is with Putin – which clearly does not inspire any confidence for a near-term resolution.

It is actually amazing that we have not seen any of the left-leaning party leaders from the rest of Europe running to Tsipras’ side as he truculently engages his paymasters. Where are all these European anti-austarians? Of course they are hiding from the Germans, hoping not to receive the same fate as Alexis. So there he sits, alone and under his last Soviet-held bridge, just like Hemingway's Robert Jordan. He is waiting to cause just a little more damage before his time is up.

In the end, there is no question that the Germans have executed a near flawless plan to humiliate and vilify Greece. The Greeks now stand as poster children for European profligacy. And they are being paraded through every town square in the EU, in shackles, as the bell tolls near the gallows for their leader. And to be sure, making an example of Greece is a probably the greatest achievement for the fiscal disciplinarians of Europe. Maastricht never had any teeth. But this exercise is impressive. It shows that fiscal excess will be squashed in Europe. The Portuguese, Spanish, and Italians are surely taking notice. And in the days that lead up to a Greek default on 30 June, and then more importantly on 20 July, these disciplinarians will surely display their power for all to see.

Oddly enough, I actually think this has been the German plan all along. With no real way to ensure fiscal discipline through the treaty, they resorted to killing one of their own in order to keep the masses in line. It explains why Merkel took out Samaras when she knew a more hostile government would surely emerge in Greece. This was masterful political manipulation.

The 1992 Maastrict Treaty created the European Union and led a few years later to the euro currency. Which I said at the time would be a disaster. And it has been. Leaders have been wrestling with its fundamental flaw almost from the beginning. The EU has no way to enforce fiscal standards on its member nations. The member nations likewise have no way to devalue the currency in their own favor. This can’t go on forever – and it won’t.

Germany, by virtue of its sheer size and its favored position in the bureaucratic scheme of things, grew wealthy partly by exporting to the European periphery: Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Ireland. (The rest of their 40–50% of exports of GDP come from exporting to the rest of Europe and the world. They have benefited massively from a currency that has been and continues to be weaker than it would be if it were just a German currency.)

The peripheral countries essentially exported all their cash to Germany (and to some extent northern Europe) in exchange for German goods. When they ran out of cash, not just because of their purchase of export goods but because of the uncompetitive nature of their bureaucratic and labor systems and the rather large unfunded government expenditures, they wanted yet more cash to continue to spend on government services. Germany and the rest of Europe offered vendor financing. German and the rest of European banks loaned money to Greeks so the Greeks could buy German goods and perpetuate their government spending habits. In the early part of the last decade, tt was a deal that was seemingly made in heaven as Greece got to borrow money at German rates and Germany got to sell products in a currency driven by the valuation of the peripheral countries.

This arrangement left Greece and the other PIIGS deep in debt. Much like the American homeowners who lived beyond their means, Greece found itself overleveraged and undercapitalized. And here we are.

Who Owns Whom?

The entire Greek drama has been an exercise in denial. In hindsight, the best solution would have been to write down all the debt when Greece got its first bailout. Everyone would have taken their lumps and moved on. This was what I advocated back in 2010.

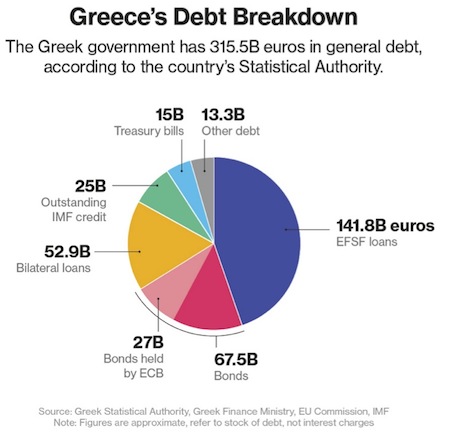

I wrote at the time (but still can’t prove) that the reason no such thing happened is that it would have left some very large European banks insolvent. Europe avoided that possibility by transferring most of Greece’s debt to the “European Financial Stability Facility,” or EFSF. It owns about 45% of Greece’s national debt. That transfer took several years and has essentially been accomplished. Greece can go completely belly-up, and the only groups that lose are essentially state actors. Bank and private debt is now minor.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-02-02/greece-seeks-third-debt-restructuring-who-s-on-the-hook-

The EFSF refinanced Greece’s debt on remarkably generous terms. The average maturity is about 32 years, and Greece pays a variable interest rate, currently about 1.5%. Most of the EFSF loans are interest-only until 2023, too. Is there anyone who wouldn’t love such terms from lenders? Sign me up.

If this sounds familiar, it should. The EFSF loans look a lot like the home equity lines of credit that left so many American homeowners in deep trouble after 2008.They are actually worse. HELOCs at least have some legal claim on collateral. The EFSF can beg and scream, but that’s about it.

The pie chart above shows how Greece’s government debt breaks down. European quasi-government organizations like EFSF, central banks, and the International Monetary Fund own the vast majority of it. Greece constantly rolls over its Treasury bills and bonds. Investors who own it are taking a big risk, but they’re also collecting premium interest rates to compensate for it.

Despite what looks like lender generosity – and a lot of austerity at home – Greece still can’t pay its debts. The immediate problem is a €1.5 billion payment to the IMF due next Tuesday, June 30. Greece will miss that payment unless someone on the other side bends. No one was willing, least of all Germany, unless Greece also tightened its belt further.

Let me see if I can summarize, from my rather voluminous readings from all facets of the media, the problems facing Greece and Europe.

1. Greece now owes 180% of GDP to a collection of mostly state lenders. Even at low rates, it is impossible for Greece to pay those loans back without somehow engineering 3-5% growth. Given that for the last five years GDP is down some 20-25%, we are clearly going the wrong direction. Many of the best and most productive Greeks, especially the young, are leaving to find jobs elsewhere; and that is not a recipe for creating new business and growth. The country is growing older because the younger are emigrating. Fewer people to pay taxes and more people needing pensions is not a recipe for growth.

Simply lending Greece more money to pay back their debt, thereby piling on an even greater burden for future generations, does kick the can down the road for the time being; but it does not solve the fundamental problem that Greece simply can’t pay. Ever. Even with essentially free money if that money comes with the requirement that there have to be more taxes and higher costs on goods.

2. The idea that reform is actually good for Greece has somehow disappeared from the picture with the coming of Syriza. I remember being in Greece about two years ago as the new, young administration took the reins. I met with government officials, most of them new to their jobs. Many were enthusiastic about their ability to change the system and reform Greece, trying to get rid of corruption and waste. Even the modest reforms they were able to put in place created a huge backlash against what was called “austerity.” (Which is what you call it when your big bad creditors want to get rid of excess government workers. All government workers become vital, especially if they are part of a big union, even if they don’t do anything.)

My visits and conversations with Greeks suggest that the Greek business environment itself is the impediment to growth. The real task, says The Economist correctly, is to “sort out the structural impediments to growth – rampant clientelism, hopeless public administration, comically bad regulations, a lethargic and unreliable justice system, nationalised assets and oligopolies, and inflexible markets for goods and services and labour.”

Let’s go through what that list actually means. Government bureaucracies tend to favor businesses already in place and create unnecessary rules for competition. The bureaucracy is hopelessly bloated, some 50% too large and heavily geared toward patronage and employing family and friends, many of whom do little or no work and collect a check regardless. The rules are such that many of the most important industries have only two actual providers of goods or services, neither of which is incentivized to compete on price. It is extremely difficult to create a new business to compete with these oligopolies.

The justice system is notoriously fickle and subject to pressure and bribes and crony capitalism. Many of the state-owned businesses, like the railroads, are hopelessly mired in losses and inefficiencies. It is actually cheaper (in terms of the system’s costs) to take a taxi across Greece than it is to ride the train, even though the train ticket is cheaper to purchase. The Greek government loses money on every passenger. Ditto for electricity and energy (which many Greeks have determined they don’t need to pay for anyway, since the energy company can’t cut off their power).

3. The IMF, headed by Christine Lagarde, who is no right-wing austerian, is insisting on attacking the bloated bureaucracy that I noted above. The previous government under Samaras had actually managed to lay off a seemingly small 12,000 government workers which were put back into place upon the election of Syriza. The IMF is insisting that be rolled back and further cuts made.

Tsipras offered other types of “reform,” calling them equivalent. What he offered was higher taxes that would make everything more costly, especially Greek tourism. The simple fact is that he cannot keep his coalition together if he caves on employment. Led by the IMF, Europe is demanding actual reform – reforms that this government cannot get through their own parliament. Tsipras is ranting to anyone who will listen that “equivalent measures” have always been accepted. And that is mostly true, except that what he is offering doesn’t deal with the real problem.

Lagarde has evidently had enough of the charade. Lending more money to Greece without real reforms that offer the Greeks a chance to work their way out of the situation is pointless. She is requiring real reforms before she opens up her checkbook. Not an unreasonable request from a lender.

4. The average age at which Greek workers receive a pension is lower than most other EU countries – 57.8 years old. Then again, this is about the same as Italy (58), is far higher than Slovenia (56.6), and is already poised to go up sharply, with the retirement age to be increased to 67 in the coming decades. (The speed with which this happens is one of the contentious points in the negotiations.) I should note that even France has already moved to change their retirement age over time to 67. Then again, the classic manipulation of the system is that those who hold some 600 “hazardous duty” jobs like hairdressers and writers are allowed to retire at 50. Many people can actually work for three years, establish a baseline, and retire with a full pension at 50 years old. Go figure why the rest of Europe is a little annoyed at having to come up with money to maintain such a system.

The Greeks are offering to slowly raise the retirement age to 67 and to make early retirement less attractive – something that needs to be done, yes, but it still doesn’t attack the structure of the system.

I should point out that the Greek population is older, on average, than the rest of Europe, and getting older. While their pension benefits are generous, their disability payments are among the lowest in Europe, and their spending on family benefits is also lower than average.

Europe is also asking that the Greek significantly raise the VAT, especially on electricity. Greek citizens would see a minimum 10% increase in their power bills, which, ironically, many of them don’t pay anyway.

5. Alexis Tsipras is in a very tough spot. If he doesn’t offer enough concessions to satisfy the creditors, Greece goes into default. If the concessions he offers are too much for the Greek parliament and voters to accept (they are balking at almost any meaningful concessions), they could (and will) toss Tsipras out on his ear.

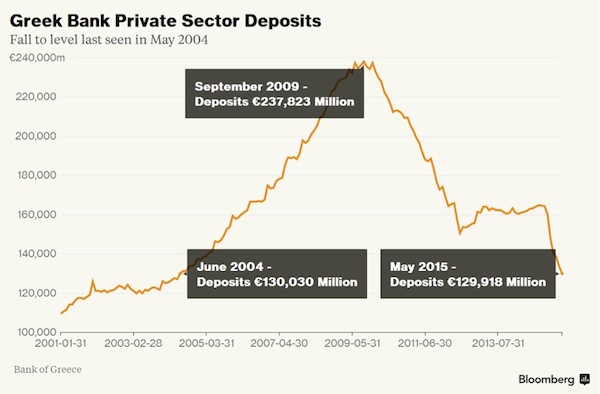

There are those that say Greece should simply walk away from the debt. Just don’t pay it, and let Europe go pound sand. It’s not that simple. First, Greek’s banking system is not waiting for the political process to play out. Fearing a cutoff from European Central Bank support and possible capital controls, Greeks are getting ready for the worst. Once again, I am hearing stories about ATM machines running out of cash. My friend, David Kotok of Cumberland Advisors, sent out this note last week:

Greece has set the new high price of “moral hazard.” Emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) from the European Central Bank now is estimated to exceed €100 billion. Every day the balance is rising. It is rising because the entire Greek banking system will collapse without ELA.

The cutting edge of moral hazard is the collapse of a banking system. That is the point in time when citizens no longer trust their institutions or government, take their money out of the bank, and go somewhere else for safety. That is the point of financial collapse.

History shows that decisions in those circumstances are driven by emotions rather than rational calculations. For those seeking safety, it becomes every citizen or business owner for themselves. In Greece, that is now happening as Greece’s debt has reached 180% of its GDP and its population is in the process of a five-year recession and a systemic collapse.

Sidebar: one of the ironies of the situation is that new car sales are increasing, as Greek see new cars as a kind of, sort of, hard asset.

Look at the following graph showing the absolute, utter collapse of Greek deposits in the last few months. This is the ultimate vote of no confidence from the country of Greece to its government. I cannot imagine why anyone would leave more than the absolute minimum in any Greek bank. If, as is quite possible, the Greeks do not agree to what the Europeans are asking (demanding), that ELA will be shut off precipitously. At that point, all assets of any Greek banks that have access to the ELA will be subject to seizure by the European Central Bank. That includes deposits. Note in the chart below that there are only some €130 billion of deposits versus maybe as much as €110 billion of ELA assistance by the time the ELA is shut off. In addition, most banks have huge nonperforming loans that would far outweigh any of their assets. Also, for the record, it is the Greek central bank that guarantees the ELA.

While deposit insurance will be instituted at some point in the future, it is not existent today. Greek depositors could lose 90-100% of their deposits overnight. Think it can’t happen? Ask Cyprus. I’ve written about the devastation that I witnessed when I went there after the bank defaults. People literally lost their life savings. That is what Tsipras is faced with. If he doesn’t do a deal, Greece is devastated far more profoundly than any people actually contemplate today. Yes, Greece can replace all of those deposits with the “new Drachma,” but what will those drachmas be worth? Or perhaps they could simply renege on the ELA (I am not quite sure of the mechanism for this), but then Greece would be without any access to foreign currency whatsoever. Utter nightmare no matter what you do.

Balancing that, Tsipras’ political life and the future of his movement is seriously at risk. As the Financial Times reports, the knives are out for Tsipras from within his own party. You have to remember that 30% of his party are communist and Trotskyites. Not exactly the sort most inclined to compromise. The final member of his coalition actually wants withdrawal from the euro. If they withhold their approval, then it’s over.

(Sidebar: to get the anti-euro party to agree to join the coalition, they had to give its leader the position of minister of defense; thus he gets to control one of the best-funded militaries in Europe. Yes, really that’s right, tiny Greece. The Greeks spend 4.3% of their budget on defense. That is in part because they look across their straits and see a well-armed Turkey. The military is a very powerful bureaucracy in Greece.)

As I write this on Friday afternoon, the headlines come across the screen saying that the Greek government rejects the creditors’ five-month extension proposal, which they say is insufficient, and further claim that they have no mandate to sign a new memorandum.

Tsipras, who was voted into office in January on a pledge to roll back years of austerity in a country battered by recession, must keep his leftist Syriza party as well as his creditors together for a deal to stick. The reason they are rejecting the offer is that Tsipras couldn’t get it through his parliament today.

I think people are forgetting what happened just six months ago. Tsipras took office on an explicit promise to roll back austerity. Now with every concession he makes, he is doing the exact opposite. Whatever concessions Tsipras offers are meaningless if he can’t convince his party – and Greek voters – that they are the best Greece can do. That’s going to be a tall order.

Right now, most analysts are fixated on repayment mechanics. I think a better question might be whether Tsipras will be around to make those decisions. What happens if Tsipras has to call snap elections sometime in the next few weeks? The IMF, ECB, Germany and everyone else will have little choice but to wait. They have to pretend they respect democracy and give the Greek voters a chance to elect someone more reasonable.

If the election puts some other party in control, they’ll need time to form a government and get up to speed on the situation. That will be another month or two. Keep this in mind when you see headlines about this being Greece’s endgame. Everyone involved would like nothing more than to kick the can down the road again. They may get their chance. (source: http://www.ekathimerini.com/4dcgi/_w_articles_wsite1_1_23/06/2015_551391)

If the Greeks agree to the latest offer before next Tuesday, their concessions will just mean more negotiations over the coming months and even more capital flight and a worse banking situation. Business confidence and growth will continue to diminish, and it will be more difficult for Greece to meet any of the rather unrealistic goals that the Europeans have set in front of them. Which will demand more concessions, etc., and more brinkmanship.

Ultimately, enough Greeks will get fed up and demand a new election and a government that can get something done – not the continued brinksmanship. Both sides are getting to the “shoot the dog and sell the farm” point.

The Greeks want to stay in the euro (memories of the drachma induce nightmares), but their entire system is uncompetitive and will trap them in a slow-growth world. They simply cannot maintain their current benefit and bureaucratic structure without assistance, and Europe is saying we are tired of giving assistance for you to maintain your unrealistic structures. Currently a majority of Greeks don’t want to change (significantly). They want the rest of Europe to continue to lend them money, but the rest of Europe is fed up. The Greeks are going to have to change before something positive can happen to Greece. It will be a wrenching change.

The Lessons Greece Can Teach Us about Europe – Madame Frexit?

Greece can teach us a few things about Europe.

- Europe (not unlike the US) will go to great lengths to avoid dealing with a structural problem and actually making changes. That means the crisis that Italy, Spain, and France will turn out to be may be a long time in coming. We are going to be dealing with the “European problem” for quite some time. A few years ago, I thought that we would see a resolution at least by the middle of the last half of this decade. I am now not so sure.

- The problem is the current system substantially inhibits growth and encourages mal-investment and creates frustrations on both sides of the political aisle. It is not just the left. There are significant right-wing (from conservative to National Socialists) movements being formed all over Europe. The largest is in France, where Marine Le Pen has moved her father’s party, the National Front Party, from an afterthought and an outlier to a significant force. They are winning elections and are very likely to contest the next presidential election, which could see the center-left and/or center-right coalitions becoming also-rans. Read what Marine Le Pen said this week on Bloomberg TV:

I will be Madame Frexit (meaning leading France out of the Eurozone) if the European Union doesn’t give us back our monetary, legislative, territorial, and budget sovereignty…. I believe that sovereignty is the twin sister of democracy. If there’s no sovereignty, there is no democracy. I’m a Democrat; I will fight it to the end to defend democracy and the will of the people…, [and] if I don’t manage to negotiate with the European Union, something I wish, [then] I will ask the French to leave the European Union. And then you’ll have to call me Madame Frexit…. Greece and France are on the same staircase; they’re not yet on the same floor. We’ll catch up with them, because the logic of the economic model imposed by the European Union always produces the same effects.

Today is the Grexit, tomorrow is the Brexit, and the day after tomorrow it will be the Frexit. At one point or another, every country who is suffering from this currency will only want one thing: escape from it or engage a battle with the European Commission.

Wow. Double wow.

- This goes to the heart of the problem. The euro is not the solution to the problems of Europe, as many thought at the beginning. It is the current cause of the problems. You cannot have a monetary union without having a fiscal union, and a fiscal union is incompatible with the notions of sovereignty in nearly every European country, especially the larger ones. There has never been a monetary union that was successful without fiscal union. Never. Not at any point in history. Ever. The euro will not be any different. The only question is the timing. Or whether some compromise can be reached on the overall debt that will allow for a fiscal union.

- And this is where I agree with my friend David Zervos. I think this is part and parcel of the German strategy. If Greece had left five years ago when I (and many others) first suggested it, Greece could now be a vibrant, growing country. European banking institutions would have been devastated and governments would have lost hundreds of billions of euros in recapitalizing their banks. Today Greece can leave, and it will be an annoyance, but Europe and the rest of the world will survive quite nicely.

Greece, on the other hand, will be devastated. If the ECB actually seizes those deposits, which it has the right to do, Greece will be impoverished for a generation. There will be no way for the country to meet its pension or government budgets. Unemployment will rise even more, and GDP will collapse.

This is precisely the lesson that Germany and the rest of the North want to deliver to the rest of Europe.

Frau Merkel has been about as generous as she can be in her offers without completely losing the German public, who are quite fed up with the Greeks. They are ready to shoot the dog and sell the farm.

- There are no winners in this standoff. It is actually quite sad, but the current impasse is a consequence of trying to secure a one-size-fits-all straitjacket monetary policy onto a very disparate group of countries and economies. Large developed economies can last longer and go further into what is seemingly an intractable situation than smaller economies can; but they, too, eventually reach an impasse.

Think Japan. Japan ran up a monster debt and has now reached the situation where it can no longer control interest rates without regular monetization of that debt. Monetization will decrease the value of their currency, but that is a consequence that they are prepared to live with. The point is that they have the option of monetizing the debt and decreasing the value of their currency. Greece and the rest of Europe don’t. Much of peripheral Europe and France will come to the point where they’re going to need that ability to monetize. Not this week or next year or even the year after that, but it will come about. And while I think the politics of Marine Le Pen are problematic in the extreme, she quite thoroughly gets the nature of the problem.

Unless something happens, something that I don’t see today, that frustration with the euro is going to continue to grow in one country after another. We are going to end up with multiple European currencies again in my lifetime. It will not be a disaster. It will simply be something for the computer to determine what currency you will pay in when you present them your credit card or send a wire in another country. The actual friction cost of exchanging currencies will come down. The values of those currencies will meander all over the place based on all sorts of factors but ultimately on government monetary policy.

Which is as it should be.

Tsipras is punting to the voters. If they say compromise, then he can tell his government to vote with the people. If the people vote the referendum down, then they leave the euro. Or that will be the effect. The situation is moving too fast now for a controllable outcome.

In Defense of Alexander Hamilton

Just a quick note on the plan to remove Alexander Hamilton from our currency. I am despondent, if not outraged, over this decision. Hamilton was arguably one of the most important of our founding fathers. He wrote almost two thirds of The Federalist Papers, which were the basis for our Constitution. He was instrumental in the achievement George Washington’s most important policies and in establishing a sound system for our government. He would have been president if he had not been killed in a duel. (I was in a museum last year here in New York that is part of the JP Morgan Chase collection and that has the actual pistols used in the duel.)

To choose to remove Jackson and leave Grant (who at one time owned slaves and who ran one of the most corrupt administrations in American history) or the populist Jackson (who was an avowed slave owner) is simply staggering. Granted, Hamilton is not a favorite among the liberal left, but to now denigrate his importance in favor of the other gentlemen mentioned above is an affront. Not that they were not also great Americans, but they simply weren’t in Hamilton’s league. This is the crassest of politics. I should note that even Ben Bernanke agrees with me, as well as many others who would not normally align with my views. I don’t know if this move can be changed, but it should be.

New York, Denver, Maine, and Boston

I am in New York for the next two weeks. We have rented an apartment in NoHo through AirBnB. It is a nice funky neighborhood, geared to the younger set, with lots of fun things to do in the evening. As it happens, my good friend Nouriel Roubini lives in the penthouse of the building, and last night he invited us to one of his famous “social events,” which featured heaps of fashionable young people. We will get together later next week to break bread and compare notes in a less hectic format. I met some very interesting Internet entrepreneurs whom I will probably follow up with as well.

July 11th I will be in Denver speaking at an industry conference for my partners at Altegris Investments. Then I will be back in New York for a day before my youngest son Trey and I once again journey to Grand Lake Stream, Maine, for the annual economists’ fishing weekend hosted by David Kotok. After that, another trip, to Whistler, British Columbia, is being discussed. And then I will head back to the Northeast, where I will spend a week in the Boston area with friends and enjoy a little R&R.

A few nights ago I was invited to a small gathering that began at The Explorers Club here in New York. One of the longtime members, Jonathan Conrad, graciously spent an hour and a half giving us a private tour of the club and its collections. If you ever get a chance, this is something you absolutely must do. The feel of history, of humanity pushing its boundaries, the sense of wonder over scientific accomplishment, permeate the collection.

Afterwards, we gathered for a dinner in a private garden on the Upper East Side, where (surprise, surprise) the conversation turned to politics of the coming presidential elections. It turns out I was invited not just for social reasons. One of the gentlemen began to press me about what it would take for a businessman to run for president of the United States. Not sometime in the future but in this cycle. It seems that he knew of someone who wanted to run. After a few more serious questions, I actually ticked off about eight or nine things, beginning with massive amounts of money. If you don’t have any name ID today, it is going to cost a great deal to buy it in Iowa and New Hampshire. Not to mention you’re already late getting a ground game, with little things like a policies platform and systems and networks of people. I was not exactly encouraging.

Later, back in the apartment, a few of us sat down, and he said he was the man planning to run. And he was ready to spend a massive amount of money to do it. (He threw out a rather astonishing number. I had no idea that anyone would be prepared to spend that amount of money, and no clue that he had that kind of money up until that point.) We did actually agree on a number of policy points.

Does he have a chance? In most years I would say that his chances would be those of (as my dad was wont to say) a snowball in hell. But this year? The race is so wide open that I can actually imagine all sorts of circumstances developing. We could actually come to the Republican convention next summer without a clear nominee. That would make it the first meaningful convention since 1976. (I have been a delegate, and it’s mostly rah-rah and fun.) After the third roll call vote, when I think all delegates will be released (at least that was the rule in the past), it could get very interesting and go in any number of directions.

We could have any number of nominees with low double-digit delegate counts and nobody with an overwhelming minority, much less majority. Could somebody come from the outside with adequate financing and present a case for a different direction? Possibly. If nothing else, that candidacy might inject a few ideas into the conversation. And this election should be all about ideas and what we need to do to organize as we move into a transformational 21st century.

Have a great week as we get ready to celebrate July 4. It’s a good time to contemplate what we would like our country look like, beginning in 2017. Find a friend or two and talk it over.

Your sad for his Greek friends analyst,

John Mauldin

subscribers@mauldineconomics.com