-- Published: Tuesday, 2 February 2016 | Print | Disqus

By John Mauldin

QE Failed, So Why Not Double Down?

Negative Short-Term Rates

The Cayman Islands and Home

“When it becomes serious, you have to lie.”

“I'm ready to be insulted as being insufficiently democratic, but I want to be serious... I am for secret, dark debates.”

“Of course there will be transfers of sovereignty. But would I be intelligent to draw the attention of public opinion to this fact?”

“If it's a Yes, we will say ‘on we go,’ and if it’s a No we will say ‘we continue.’”

“We all know what to do, we just don't know how to get re-elected after we’ve done it.”

– All quotes from Jean-Claude Juncker, prime minister of Luxembourg and president of the European Commission

I’ve been busily writing a letter on oil and energy, but in the middle of the process I decided yesterday that I really needed to talk to you about the Bank of Japan’s “surprise” interest-rate move to -0.1%. And I don’t so much want to comment on the factual of the policy move as on what it means for the rest of the world, and especially the US.

But before we go there, I also want to note that today is Iowa, and so we’re about to turn a big corner in what is fast becoming one of the wackiest years in American political history. I’m going to sit down tonight after the caucus results come in and write to you again, for a special edition of Thoughts from the Frontline that will hit your inbox tomorrow. Along with Iowa, I want to delve into the issue of what a “brokered convention” would mean for the Republican Party, and what one would look like.

QE Failed, So Why Not Double Down?

I have been steadfastly maintaining that the Bank of Japan was going to augment its quantitative easing stance sometime this spring. Inflation has not come close to their target, and the country’s growth is dismal, to say the least. So the fact that the Bank of Japan “did something” was not a surprise. I will however admit to being surprised – along with the rest of the world – that they chose to do it with negative interest rates. Especially given the fact that Kuroda-san had specifically said in testimony to parliament only a few days earlier that he was not considering negative interest rates.

While this development is significant for Japan, of course, I think it has broader implications for the world; and the more I think about it, the more nervous I get. First let’s look at some facts.

Conspiracy theorists will love this Bank of Japan timeline:

Jan 21 – Kuroda emphatically tells Japanese parliament he is not considering NIRP.

Jan 22 – Kuroda flies to Davos.

Jan 29 – Kuroda enthusiastically embraces NIRP and promises more of it if needed.

So, whom did he talk to in Davos, and what did they say to change his mind?

In an email exchange I had with Rob Arnott about the Bank of Japan, he reminded me of that wonderful Jean-Claude Juncker quote wherein he states, “When it gets serious, you have to lie.” Which, given my theme, ties in well with another of his quotes: “I'm ready to be insulted as being insufficiently democratic, but I want to be serious... I am for secret, dark debates.”

Haruhiko Kuroda, according to reports, came back from that testimony to parliament and instructed his staff to prepare a set of documents outlining all the potential choices, along with their pros and cons, to be ready for the next BOJ meeting when he got back from Davos.

To pretend that he walked into that meeting without having had lengthy talks about whether to pursue negative interest rates strains credulity – and it just wouldn’t be very Japanese. The conduct of business and governance in Japan relies heavily on a process called nemawashi, or “stirring the roots”: the outcome of any important meeting is decided ahead of time through private discussions among those who will participate. In any case, the vote to take rates into negative territory came down to a razor-thin 5 to 4, so you can be damn sure Kuroda knew exactly who was with him and who was not. You do not take a vote like that and lose – not and remain chairman.

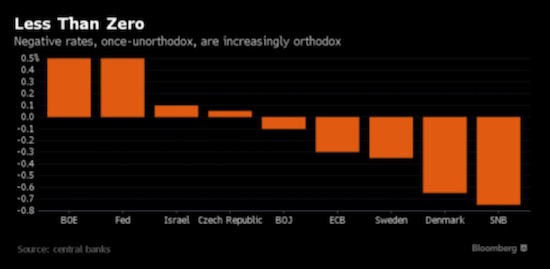

The entire world has been watching the European experiment. Four countries in Europe are now at negative rates (see graph below). Two others are so close that it hardly makes a difference. The Federal Reserve and the Bank of England are both at 0.5%.

Switzerland, Denmark, and Sweden all lowered their rates to make their currencies less attractive, since the franc, the krone, and the krona had appreciated too strongly against the faltering euro. Meanwhile, the ECB is trying to stimulate the Eurozone economy and create inflation. The question is, exactly how many unintended consequences will there be with negative rates?

(For the record, to my knowledge none of the banks charge negative rates on required reserves, just on excess reserves. Excess reserves are defined as money on deposit at a bank in excess of whatever the regulators think is necessary to fund the bank’s operations. The concept of excess reserves is a totally artificial one. Aggressive banks will keep reserves as low as possible in order to make maximum returns, and conservative banks will of course hold more reserves. Where do you want to put your money? Then again, if you’re looking to borrow money, which bank do you go to?)

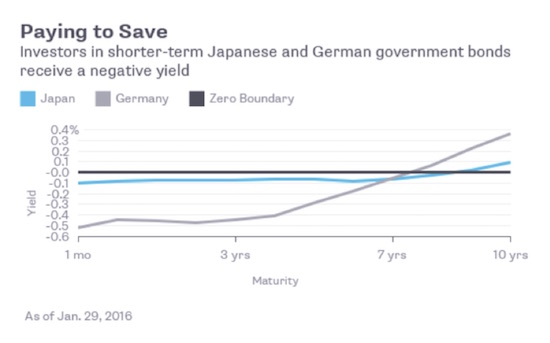

The people that NIRP (negative interest rate policy) hurts the most are those who are living on their savings or trying to grow their retirement accounts, but apparently our all-wise central banks have decided that a little pain for them is worth the potential for growth in the long run. Savers in both Germany and Japan have to buy bonds out past seven years just to see a positive return. Some 29% of European bonds now carry a negative interest rate. Recently we have seen Japanese corporate bonds paying negative interest.

Sidebar: if I am a Japanese corporation and somebody is willing to pay me to lend me money, why am I not backing up the truck and seeing how much the market will give me? Then turn around and invest the money in fixed-income assets? Just asking…

Whatever turmoil the Bank of Japan had already created was apparently not enough to concern a majority of its board, so they have moved to negative interest rates.

Let’s shift from Japan to the US. Last week, former Fed chair Ben Bernanke said in an interview that the Fed should consider using negative rates to counter the next serious downturn. “I think negative rates are something the Fed will and probably should consider if the situation arises,” he said.

The same story at MarketWatch mentioned that former Fed Vice-Chairman Alan Blinder has already suggested using negative interest rates for overnight deposits. And Janet Yellen, who said in her confirmation testimony to Congress in 2013 that the potential for negative interest rates to cause disruption was significant, now says they are an option the Fed would consider.

We often refer to the herd mentality when we talk about investors. Economic academicians and central bankers are equally prone to bovine behavior. Theirs is a slow-moving herd, to be sure, but it raises much dust as it lumbers.

One of the biggest “aha” moments of my life came as I listened to David Blanchflower, former Bank of England governor (during last decade’s financial crisis), in a debate a few summers ago at Camp Kotok, the Maine fishing retreat I attend every August. The debate centered around whether the Fed and the Bank of England should have engaged in quantitative easing.

Blanchflower shared a rather chilling description of what was going on at the time and made the point that, as bad off as the banks were in the US, they might have been worse off in England. They were literally days from a total collapse. Liquidity had to be provided – and that is the one true and worthwhile purpose of central banks (but then they double down). Blanchflower’s argument was that you could not sit in the BOE’s meetings, see how impossible the situation was, and do nothing. You had to act.

In such a predicament you rely upon your best instincts and education and training, and then you act. And you hope that the actions you take do more good than harm.

Now, let’s fast-forward right into the future and the next recession in the US, which will probably be part and parcel of a global recession. Major central banks everywhere will be lowering rates, engaging in quantitative easing, and in some cases going even deeper into negative interest rates.

You sit on the Federal Open Market Committee. Almost everyone in the room with you is a committed Keynesian. That is the bulk of your training and experience, too, and everyone agrees with you. You are going to take actions that are in alignment with your theoretical understanding of how the world works.

And your theory says that you need to reduce the cost of money so that people will borrow and spend. You know that doing so will hurt savers, but it is more important that you get the economy moving again.

What do you do? You are hearing from everyone that the dollar is too strong and is hurting US business. You worry about the unintended consequences of taking the world’s reserve currency into negative-interest-rate territory, but the staff economists are handing you papers that argue persuasively that the best possible alternative is negative rates. So you throw in the towel.

Which is pretty much the situation Kuroda-san was in when he came back from Davos – his staff economists (who have had much the same training as the Fed economists have) were waiting for him. Yes, and he may have received assurances from the central bankers of other countries who have already gone negative, but you don’t make such a decision based on a few conversations. Kuroda had been thinking about negative rates for a long time.

You have to understand that in the world of truly elite economists, everyone knows everyone. Many of them went to the same schools, and they regularly talk at conferences, in private meetings, and by phone and email. I can guarantee you that they are talking about if and when it might be necessary for the US to go down the path of negative interest rates. The policy makers are not committed to following that path, but they are certainly talking about it. When they tell us it’s an option, we need to take them seriously.

I have been in the room (under Chatham House rules, so I cannot reveal when or where or who) with some of the world’s most elite economists (Nobel laureates, etc.), who were privately advocating that the US should pursue not just 2% but 4% inflation. This is not the language I hear when they are interviewed in public. They very well get the seriousness of our current economic predicament, but their academic theory tells them that the way to resolve that predicament is with more quantitative easing and even lower rates.

You need to understand that economists have faith in their theories in the same way that many people have faith in their religion.

We need to seriously contemplate and war-game in our investment committee meetings, in meetings with our investment advisors, etc., what negative interest rates would mean for our portfolios. You do not want to wait until the last minute, when negative rates are already an adopted policy, to try to react. NIRP is not going to happen in the US this week or this month, and I seriously doubt we’ll even see negative rates this year; but if it’s on the table at the Federal Reserve, then you need to have it on the table as a distinct possibility.

Negative Short-Term Rates

Four months ago Lacy Hunt wrote about the negative consequences of a negative interest-rate policy. I sent that to you as an Outside the Box, but let’s excerpt a few paragraphs:

The Fed could achieve negative rates quickly. Currently the Fed is paying the depository institutions 25 basis points for the $2.5 trillion in excess reserves they are holding. The Fed could quit paying this interest and instead charge the banks a safekeeping fee of 25 basis points or some other amount. This would force yields on other short-term rates downward as the banks, businesses and households try to avoid paying for the privilege of holding short-term assets.

No guarantees exist that such an action would be efficacious. Heavily indebted economies are not very responsive to such small changes in short-term interest rates. Many negatives would outweigh any initially positive psychological response. Currency in circulation would rise sharply in this situation, which would depress money growth. The Fed may try to offset such currency drains, but this would only be achievable by further expanding the Fed’s already massive balance sheet. If financial markets considered such a policy inflationary over the short-term, the more critically sensitive long-term yields could rise and therefore dampen economic growth.

An extended period of negative interest rates would lead to many adverse unintended consequences just as with QE and ZIRP. The initial and knockoff effects of negative interest rates would impair bank earnings. Income to households and small businesses that hold the vast majority of their assets with these institutions would also be reduced. As time passed a substantial disintermediation of funds from the depository institutions and the money market mutual funds into currency would arise. The insurance companies would also be severely challenged, although not as quickly. Liabilities of pension funds would soar, causing them to be vastly underfunded. The implications on corporate capital expenditures and employment can simply not be calculated. The negative interest might also boost speculation and reallocation of funds into risk assets, resulting in a further misallocation of capital during a time of greatly increased corporate balance sheet and income statement deterioration.

Lakshman Achuthan posted an essay this week (which I sent to Over My Shoulder readers) in which he outlines why growth in the US will slow to 1% over the next decade. He talks about the economic establishment’s betting everything on policies of quantitative easing and low rates. And by everything he means the global economy. Everything. Quoting:

The math is too simple to ignore. Potential labor force growth will average ½% per year for at least the next decade, and US labor productivity growth may well stay around ½% a year, its rough average for the last five years. These add up to 1% long-term potential GDP growth, which actual GDP growth can surpass only temporarily during a cyclical upswing – and certainly not during a cyclical slowdown. This is a challenging problem, with demographics practically set in stone, and a boost to productivity growth realistically possible only in the long run.

Consequently, after years of ZIRP and QE attempting to pull demand forward from the future, central banks are increasingly powerless when it comes to the economy itself. They can “print” money, but not economic growth. The world is watching, so those who are thought to walk on water cannot afford to be seen to have feet of clay.

If U.S. growth keeps slowing this year, recession risk will rise, and the Fed will likely revisit ZIRP, in one way or another. The failure of Abenomics is not inevitable, but appears increasingly probable. And while China is not yet facing a hard landing, growth continues to slow, raising legitimate concerns about its leaders’ capability to avoid one.

By clinging to unrealistic growth expectations, the economic establishment has effectively bet everything on the success of these grand experiments, and the risk of losing that bet is rising inexorably. Ultimately, only policies that genuinely address the challenges of demographics and productivity have a chance to succeed. It is high time for that discussion to begin.

Lakshman is right, but we are not really going to get that discussion, except in the context of Keynesian policy. Which is at the very heart of the problem. There would have to be an admission of failure by the economic establishment in order for there to be a serious discussion. It would be like asking the Pope and all his priests to convert to another theological viewpoint. Here and there it could happen, but a mass shift?

In the world of the leading economists and central bankers, “everyone” believes what “everyone” knows to be true. All their research agrees with them, and any that doesn’t is labeled as flawed. Any empirical evidence that shows quantitative easing hasn’t been working is ignored or explained away, even when it is presented by outstanding academic economists. No, quantitative easing didn’t work because we didn’t do enough of it. Negative interest rates aren’t working because we haven’t gone low enough.

Clearly, QE has not worked. We have not had one year of 3%+ growth since the Great Recession and are barely averaging 2%. Yes, if your measure is the stock market and other financial assets that have inflated, then QE has worked quite well. But the boost QE was supposed to deliver just hasn’t reached Main Street. One of the basic tenets of QE and other related policies is that if you want to increase consumption, you lower the cost of borrowing. But if out-of-control borrowing was the original problem, then QE as a solution is kind of like drinking more whiskey in order to sober up. And if you reduce the earnings of those who are savers so that they are no longer able to spend, the whole purpose of the original project – to foster economic growth – is defeated. But we can’t acknowledge that, because if we did, we’d have to admit that our theories don’t work. And we all know, because God knows, that our theories are correct.

The theme of negative interest rates is one we are going to come back to again and again. We have little idea what NIRP’s unintended consequences to our portfolios and to our businesses will ultimately be, but we had better start thinking them through.

I know we have been pushing early registration for my conference rather heavily in the past few weeks, and I want to thank the large number of people who have already signed up. It is going to be a dynamite conference. I really am putting together a fabulous lineup to discuss critical economic trends and policies like the ones we covered in this letter. And we will have a fair representation of those who believe that QE has been precisely what was needed and has been successful. We will get both sides of the argument. I am really not so much interested in trying to determine the correctness of one belief or another at the conference as I am in discerning the practical implications for our investment portfolios and discussing how those of us who are in the money management business need to position our clients. NIRP-proofing our portfolios is a most vexing conundrum.

The Cayman Islands and Home

Wednesday we fly to the Cayman Islands, where I’ll speak at the Cayman Alternative Investment Summit, one of the biggest hedge fund and alternative investment gatherings outside of the US. They have an impressive lineup of speakers, and I note that this year the celebrity guest speakers are Jay Leno and the star of my all-time favorite movie, Trading Places – Jamie Lee Curtis. That should be fun. I just looked through the speaker list and noticed that Pippa Malmgren, who will also be at my SIC conference, is speaking, and it will be fun to catch up with her again. I will be on a panel (moderated by KPMG chief economist Constance Hunter) with old and brilliant friends Nouriel Roubini and Raoul Pal. At least I know that with those two guys there is no need to wear a tie. Don’t tell the conference organizers this, but I will probably be paid more per word for this panel than I have ever been paid in my life. That is because with these three I will be lucky to get a word in edgewise.

Theoretically, unless the Chinese central bank decides to go to negative rates, I will write about oil next week.

Your going to watch the Iowa returns closely analyst,

John Mauldin

subscribers@MauldinEconomics.com

| Digg This Article

-- Published: Tuesday, 2 February 2016 | E-Mail | Print | Source: GoldSeek.com