-- Published: Monday, 18 July 2016 | Print | Disqus

By John Mauldin

The Implications of the Coup in Turkey

The Age of No Returns

The Big Conundrum

Yellen Changes the NIRP Tune

When Average Is Zero

Maine, New York, Montana, Iceland (?), and Denver

“A bank is a place where they lend you an umbrella in fair weather and ask for it back when it begins to rain.”

– Robert Frost

“Money won’t create success. The freedom to make it will.”

– Nelson Mandela

I am going to interrupt my regular letter for a few pages, as the events in Turkey in the last 24 hours compel me to offer a few thoughts. Fortunately for you, patient reader, rather than getting my own less-than-expert analysis, you will have that of George and Meredith Friedman, members of the Mauldin Economics team who have been doing geopolitical analysis for 40 years and who have serious connections in Turkey. We will open this week’s letter by looking at George’s brief take of the actual meaning of what is going on in Turkey, as events continue to play out there.

George has an experienced team of analysts who write for his firm Geopolitical Futures. They are seemingly on 24-hour call, and they have highly placed connections all around the world, so George’s team can gain deep insights into whatever is happening in a country on an almost immediate basis. I am privileged in that I can pick up the phone and get to him whenever I need a deeper dive into what is going on in the world. After George’s brief analysis we’ll get into a few economic thoughts as well. So let’s start with George.

The Implications of the Coup in Turkey

Mid-afternoon on Friday in the US (late evening in Turkey), we started to receive reports that tanks were deploying in Istanbul and two bridges over the Bosporus had been closed by Turkish Army troops. A bit later, we got reports that armor had been deployed in Ankara, Turkey’s capital, and that there was fighting going on between Turkish Army special forces and national police around the parliament. Turkish F-16s were seen in large numbers in the skies. A military coup was underway.

Military coups were fairly common in the world thirty or forty years ago. Turkey itself last had a coup in 1980. Having a full-dress coup, with tanks in the streets and government buildings under attack, seemed archaic. Yet here it was. For us, it was a complete surprise. True, the Army was Turkey’s institutional guarantee of secularism. Kemal Ataturk’s post-World War I revolution was dedicated to secularism, to the point that head scarves on Muslim women were banned for decades. When the AKP, Recep Erdogan’s party, won the election of 2003 and pledged to speak for devout Muslims’ interests, a clash with the Army was inevitable. Erdogan managed this challenge with surprising skill and even ease. He first blocked and then broke the Army’s power. In spite of grumblings, and some arrests over coups that never quite happened, Erdogan made the military subordinate to his wishes.

Yet here were tanks in the street. Somehow, certainly out of our sight – and out of the sight of people who now say they always knew it was coming – a coup had been organized. Organizing a coup is not easy. It has to be carefully planned many weeks before. Many thousands of troops, as well as tanks, helicopters, and all the rest, must suddenly and decisively appear in the streets and take over. And all of this planning has to take place in complete secrecy, because without the element of surprise there is no coup.

This began our first conversation: How did the military organize a coup without a word of it leaking? Turkey’s security and intelligence services are professional and capable, and watching the military is one of their major jobs. A coup requires endless meetings and preparation. In this day of intrusive surveillance, how did the military keep its intentions under wraps?

The only explanation we could find is that the intelligence organizations must have been in on it. If so, then the game was over for Erdogan. A source we had in the military, someone fairly senior, said he had no idea the coup was happening. He did know that Erdogan was at a hotel in Marmaris, on the Mediterranean. The coup was planned while Erdogan was away from Ankara and it would be easy to isolate and arrest him. Perfect planning, without a leak.

A few hours after the coup began, troops loyal to the coup makers entered some television studios and newspaper offices and had broadcasters announce that a coup had taken place and that the traditional secular principles of Kemal Ataturk had been restored. Since we had been told by our sources that the coup was being run by very senior officers (though not the chief of staff), it appeared to us that it had succeeded. Erdogan was being held in a resort town, apparently unable to return to Istanbul or Ankara, as airports were held by the military. The communication centers had been secured. There were even troops in Taksim Square, the major gathering place in Istanbul, which meant the city was saturated. The coup looked as if it was nearing its end.

Then suddenly everything changed. Erdogan started making statements via FaceTime on Turkish TV NTV. Well, instead of Erdogan’s being arrested, as we’d been led to believe, maybe it was just that troops were outside his hotel, and he was still free enough to do this. Sloppy work on the part of the coup. Then Erdogan got on a plane and flew in to Istanbul’s Ataturk Airport, which had reportedly been secured by the military conducting the coup. Again, sloppy work. It was clear that Erdogan was free, because he was making threats. Then we got reports of Turkish troops surrendering to policeman in Taksim Square, and the bridges that had been closed were abandoned by troops and reopened. Erdogan ordered loyal F-16s to shoot down helicopters attacking the parliament building in Ankara.

The situation morphed from business as usual to a successful coup to a failed coup in a matter of hours. And we still had no explanation as to why the people staging the coup hadn’t been detected by the intelligence services.

It is time for “tin foil.” We could speculate that Erdogan wanted the coup. He knew he could defeat it, and the attempt now gives him the justification to utterly purge the army. Perhaps he went to Marmaris for his own security. Then, as I write this, there are reports from the Greek military that a Turkish frigate was seized by Turkish troops opposed to Erdogan, that the Turkish Navy’s commanding officer was being held hostage, and that Erdogan had sent a text urging all Turks into the streets. The coup is either over, or it’s not. The coup planners either evaded detection, or they were allowed to walk into Erdogan’s trap. All that will become clearer in the next few hours. I write this Saturday morning, and John will send it out a few hours later to you as part of his letter.

But there are deeper meanings and geopolitical implications of the coup attempt. We know that there are deep tensions between Turkey’s secular population, centered in Istanbul and long grounded and comfortable in Ataturk’s philosophy, and Erdogan’s more religious supporters in Anatolia and elsewhere. (Anatolia is the rather vast, less densely populated, region east of the Bosporus and is generally more conservative but also includes a large Kurdish region and a few other minority ethnic groups.)

These religious minorities of Anatolia had been marginalized since World War I. Erdogan came to power intending to build a new Turkey. He understood that the Islamic world had changed, that Islam was rising, and that Turkey could not simply remain a secular power. He understood that domestically and in terms of foreign policy. There have been persistent reports that Turkey is at least allowing IS to use its financial system, selling its oil in Turkey, and moving its people through Turkey. Erdogan has been, until recently, reluctant to attack them. He shifted his strategy in recent months, resulting in IS attacks on Turkey, apparently in retaliation.

Erdogan is caught between two forces. One is a Jihadist faction that it seems he has tried to manage, to deflect it from hitting Turkey. This effort has put him at odds with the United States and Russia simultaneously. He has also been under pressure from a domestic secular faction appalled by his strategy. Recently the strategy shifted. He reopened relations with Israel and apologized to Russia. He got rid of what many saw as a pro-Islamist prime minister. He appeared to be trying to rebalance his policy. The people who staged the coup likely saw these moves as weakness and sensed an opening.

It should be remembered that Turkey has become the critical country in its greater region. It is the key to any suppression of IS in Syria and even in Iraq. It is the pivot point of Europe’s migrant policy. It is challenging Russia in the Black Sea. The United States needs Turkey, as it has since World War II; and Russia can’t afford a confrontation with it. Neither country likes Erdogan, but it is not clear that either country has options. Interestingly, the Russian foreign minister, Lavrov, and the US Secretary of State, John Kerry, were having marathon meetings on Syria as the coup was taking place.

The room for conspiracy theories is endless now, because there actually were conspiracies – and likely conspiracies within conspiracies. So let’s end with the obvious. Turkey affects the Middle East, Europe, and Russia. It is also a significant force in shaping jihadist behavior. Erdogan has been increasingly erratic in his behavior, as if trying to regain his balance. The coup meant that some within the military thought he was vulnerable. His supporters are now trying to reestablish control.

The coup appears over, but the repercussions of follow-on actions are not. Erdogan will unleash as much political intimidation as he can and conduct political and military purges to frighten the military. However, reigns of terror don’t work well if they frighten men with guns, making them feel they have nothing to lose by fighting back. There is no evidence that major military formations came to Erdogan’s aid. The military seems divided among those who staged the coup, those who were neutral, and the national police who backed Erdogan. Though Erdogan is a master of appearing stronger than he is, he looked weak calling for people to come into the streets to demonstrate their support. But he can’t afford to look weak, so he has to make a decisive countermove. If he can.

+++++++++

George has been sending updates on Turkey to his own Geopolitical Futures subscribers. If you are interested in the meanings behind the geopolitical events that are shaping today’s world, we are still offering George’s letter at a deeply discounted rate, which you can get here.

At a minimum, you should subscribe to This Week in Geopolitics, the free weekly letter that George writes for Mauldin Economics. For those of you who aren’t familiar with George’s massive body of work, this is a way to freely avail yourself of his thinking and then decide whether you too need an even deeper dive. I find him indispensable.

Also, George did a quick video on Turkey yesterday that is available here.

Now to our regularly scheduled letter.

The Age of No Returns

The enemy is coming. Having absorbed Japan to the west and Europe to the east, negative interest rates now threaten North America from both directions. The vast oceans that protect us from invasions won’t help this time.

Someday I want to get someone to count the number of times I’ve mentioned central bank chiefs by name in this newsletter since I first began writing in 2000, and we should graph the mentions by month. I suspect we’ll find that the number spiked higher in 2007 and has remained at a high plateau ever since – if it has not climbed even higher.

That’s our problem in a nutshell. We shouldn’t have to talk about central banks and their leaders every time we discuss the economy. Monetary policy is but one factor in the grand economic equation and should certainly not be the most important one. Yet the Fed and its fellow central banks have been hogging center stage for nearly a decade now.

That might be okay if their policies made sense, but abundant evidence says they do not. Overreliance on low interest rates to stimulate growth led our central bankers to zero interest rates. Failure of zero rates led them to negative rates. Now negative rates aren’t working, so their ploy is to go even more negative and throw massive quantitative easing and deficit financing at the balky global economy. Paul Krugman is beating the drum for more radical Keynesianism as loudly as anyone. He has a legion of followers. Unfortunately, they are in control in the halls of monetary policy power.

Our central banks are one-trick ponies. They do their tricks well, but no one is applauding, except the adherents of central bank philosophy. Those of us who live in the real economy are growing increasingly restive.

Today we’ll look at a few of the big problems that the Fed and its ilk are creating. As you’ll see, I think we are close to the point in the US where a significant course change might help, because our fate is increasingly locked in. I believe Europe and Japan have passed the point of no return. That means we should shift our thinking toward defensive measures.

The Big Conundrum

The immediate Brexit shock is passing, for now, but Europe is still a minefield. The Italian bank situation threatens to blow up into another angry stand-off like Greece, with much larger amounts at stake. The European Central Bank’s grand plans have not brought Southern Europe back from depression-like conditions. I cannot state this strongly enough: Italy is dramatically important, and it is on the brink of a radical break with European Union policy that will cascade into countries all over Europe and see them going their own way with regard to their banking systems. Italian politicians cannot allow Italian citizens to lose hundreds of billions, if not trillions, of euros to bank “bail-ins.” Such losses would be an utter disaster for Italy, resulting in a deflationary depression not unlike Greece’s. Of course, for the Italians to bail out their own banks, th ey will have to run their debt-to-GDP ratio up to levels that look like Greece’s. Will the ECB step in and buy Italy’s debt and keep their rates within reason? Before or after Italy violates ECB and EU policy?

The Brexit vote isn’t directly connected to the banking issue, but it is still relevant. It has emboldened populist movements in other countries and forced politicians to respond. The usual Brussels delay tactics are losing their effectiveness. The associated uncertainty is showing itself in ever-lower interest rates throughout the Continent.

That’s the situation to America’s east. On our western flank, Japan had national elections last weekend. Voters there do not share the anti-establishment fever that grips the rest of the developed world. They gave Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his allies a solid parliamentary majority. Japanese are either happy with the Abenomics program or see no better alternative.

His expanded majority may give Abe the backing he needs to revise Japan’s constitution and its official pacifism policy. Doing so would be less a sign of nationalism than a new economic stimulus tool. Defense spending that more than doubles – as it is expected to do – will give a major boost to Japan’s shipyards, vehicle manufacturing, and electronics industries.

The Bank of Japan’s negative-rate policy and gargantuan bond-buying operation will now continue full force and may even grow. Whether the program works or not is almost beside the point. It shows the government is “doing something” and suppresses the immediate symptoms of economic malaise.

The Bank of Japan is the Japanese bond market. They are buying everything that comes available, and this year they will need to cough up an extra ¥40 trillion ($400 billion) just to make their purchase target, let alone increase their quantitative easing in the desperate attempt to drive up inflation. What is happening is that foreign speculators are becoming some of the largest holders of Japanese bonds, and many Japanese pension funds and other institutions are required to hold those bonds, so they aren’t selling. The irony is that the government is producing only about half the quantity of bonds the Bank of Japan wants to buy. Sometime this year the BOJ is going to have to do something differently. The question is, what?

Okay, for you conspiracy theorists, please note that “Helicopter Ben” Bernanke was just in Japan and had private meetings with both Prime Minister Abe and Kuroda, who heads the Bank of Japan.

Given the limited availability of bonds for the BOJ to buy, and that they’ve already bought a significant chunk of equities and other nontraditional holdings for a central bank, what are their other options?

Perhaps Japan could authorize the BOJ to issue very-low-interest perpetual bonds to take on a significant portion of the Japanese debt. That option has certainly been a topic of discussion. It’s not exactly clear how you get people to give up their current debt when they don’t want to, or maybe the BOJ just forces them to swap out their old bonds for the new perpetual bonds, which would be on the balance sheet of the Bank of Japan and not counted as government debt. That’s one way to get rid of your debt problem.

But that doesn’t give Abe and Kuroda the inflation they desperately want. Putting on my tinfoil hat (Zero Hedge should love this), the one country that could lead the way in actually experimenting with a big old helicopter drop of money into individual pockets is Japan. And Ben was just there… This bears watching. Okay, I am now removing my tinfoil hat.

Yellen Changes the NIRP Tune

I have been saying on the record for some time that I think it is really possible that the Fed will push rates below zero when the next recession arrives. I explained at length a few months ago in “The Fed Prepares to Dive.”

In that regard, something important happened recently that few people noticed. I’ll review a little history in order to explain. In Congressional testimony last February, a member of Congress asked Janet Yellen if the Fed had legal authority to use negative interest rates. Her answer was this:

In the spirit of prudent planning we always try to look at what options we would have available to us, either if we needed to tighten policy more rapidly than we expect or the opposite. So we would take a look at [negative rates]. The legal issues I'm not prepared to tell you have been thoroughly examined at this point. I am not aware of anything that would prevent [the Fed from taking interest rates into negative territory]. But I am saying we have not fully investigated the legal issues.

So as of then, Yellen had no firm answer either way.

A few weeks later she sent a letter to Rep. Brad Sherman (D-CA), who had asked what the Fed intended to do in the next recession and if it had authority to implement negative rates. She did not directly answer the legality question, but Bloomberg reported at the time (May 12) that Rep. Sherman took the response to mean that the Fed thought it had the authority. Yellen noted in the letter that negative rates elsewhere seemed to be having an effect. (I agree that they are having an effect; it’s just that I don’t think the effect is a good one.)

Fast-forward a few more weeks to Yellen’s June 21 congressional appearance. She took us further down the rabbit hole, stating flatly that the Fed does have legal authority to use negative rates, but denying any intent to do so. “We don't think we are going to have to provide accommodation, and if we do, [negative rates] is not something on our list,” Yellen said.

That denial came two days before the Brexit vote, which we now know from FOMC minutes had been discussed at a meeting the week earlier. But I’m more concerned about the legal authority question. If we are to believe Yellen’s sworn testimony to Congress, we know three things:

- As of February, Yellen had not “fully investigated” the legal issues of negative rates.

- As of May, Yellen was unwilling to state the Fed had legal authority to go negative.

- As of June, Yellen had no doubt the Fed could legally go negative.

When I wrote about this back in February, I said the Fed’s legal staff should all be disbarred if they hadn’t investigated these legal issues. Clearly they had. Bottom line: by putting the legal authority question to rest, the Fed is laying the groundwork for taking rates below zero. And I’m sure Yellen was telling the truth when she said last month that they had no such plan.

Plans can change. The Fed always tells us they are data-dependent. If the data says we are in recession, I think it is very possible the Fed will turn to negative rates to boost the economy. Except, in my opinion, it won’t work.

When Average Is Zero

Now, I am not suggesting the Fed will push rates negative this month or even this year – but they will do it eventually. I’ll be surprised if it doesn’t happen by the end of 2018.

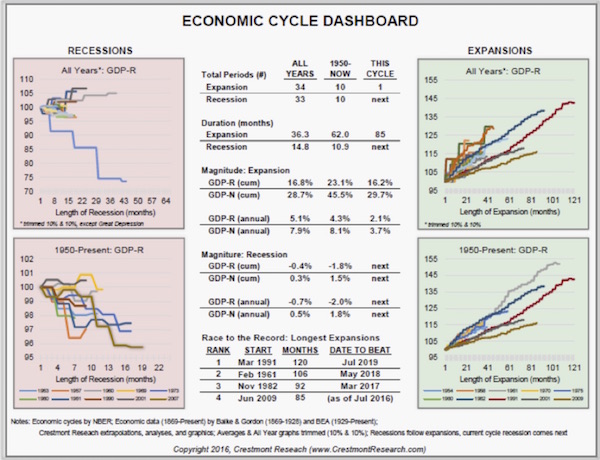

A prime reason the next recession will be severe is that we never truly recovered from the last one. My friend Ed Easterling of Crestmont Research just updated his Economic Cycle Dashboard and sent me a personal email with some of his thoughts. Here is his chart (click on it to see a larger version).

The current expansion is the fourth-longest one since 1954 but also the weakest one. Since 1950, average annual GDP growth in recovery periods has been 4.3%. This time around, average GDP growth has been only 2.1% for the seven years following the Great Recession. That means the economy has grown a mere 16% during this so-called “recovery” (a term Ed says he plans to avoid in the future).

If this were an average recovery, total GDP growth would have been 34% by now instead of 16%. So it’s no wonder that wage growth, job creation, household income, and all kinds of other stats look so meager. For reasons I have outlined elsewhere and will write more about in the future, I think the next recovery will be even weaker than the current one, which is already the weakest in the last 60 years – precisely because monetary policy is hindering growth.

Now combine a weak recovery with NIRP. If, in the long run, asset prices are a reflection of interest rates and economic growth, and both those are just slightly above or below zero, can we really expect stocks, commodities, and other assets to gain value?

The upshot is that whatever traditional investment strategy you believe in will probably stop working soon. Ask European pension and insurance companies that are forced to try to somehow materialize returns in a non-return world of negative interest rates.

All bets may be off anyway if the latest long-term return forecasts are correct. Here’s GMO’s latest 7-year asset class forecast:

See that dotted line, the one that not a single asset class gets anywhere near? That’s the 6.5% long-term stock return that many supposedly wise investors tell us is reasonable to expect. GMO doesn’t think it’s reasonable at all, at least not for the next seven years.

If GMO is right – and they usually are – and you’re a devotee of any kind of passive or semi-passive asset allocation strategy, you can expect somewhere around 0% returns over the next seven years – if you’re lucky.

Note also that nearly invisible -0.2% yellow bar for “U.S. Cash.” Negative multi-year real (adjusted for inflation) returns from cash? You bet. Welcome to NIRP, American-style. Would you like that with fries?

The Fed’s fantasies notwithstanding, NIRP is not conducive to “normal” returns in any asset class. GMO says the best bets are emerging-market stocks and timber. Those also happen to be thin markets that everyone can’t hold at once. So, prepare to be stuck.

Next week we will look at what current and future monetary policies mean to pension funds and taxpayers, not to mention retirees and those who would like to retire sometime in the next 10 years.

Maine, New York, Montana, Iceland (?), and Denver

I am finishing up this letter from Las Vegas, dashing off the final part before I go deliver a speech. We fly back tomorrow, and then I’ll be home for about 17 days before heading off to Maine for the annual Camp Kotok gathering of economists, analysts, media, and assorted other ne’er-do-wells to fish and share a few adult beverages. In most groups where you gather 50 fishermen, the biggest whoppers are about the fish that got away. In the case of this assembly in Maine, the biggest tall tales are about our views on the economy. Let’s just say that not everyone agrees; and over the 10 years that my son Trey and I have been attending, I have found that trying to persuade the rest of this bunch about the proper way to view the economy and markets is a thankless, hopeless task. Nevertheless, it is a duty that I willingly take up, year after year, along with my fly rod.

After Camp Kotok I fly to New York for a few days before traveling cross country to Flathead Lake, Montana, to spend time with my business partner and good friend Darrell Cain and a bunch of young rocket scientists. With their help I’ll research a chapter on the future of space for my upcoming book and try to write a few other chapters as well. Note to my publishers: I actually did finish the last chapter and final edits of Code Red at this very retreat, so it is possible to get some work done there.

Then I have been offered an opportunity to go to Iceland and research the future of energy and a few other topics for a few days in the middle of August. We’ll see if that materializes.

I will be in Denver on September 14 for the S&P Dow Jones Indices Denver Forum. If you are an advisor/broker and are looking for ideas on portfolio construction, I will be there along with some other friends to offer a few suggestions. Sometime in the fourth quarter, I will actually go public with what I think is an innovative way to approach portfolio construction and asset class diversification. This approach makes more sense for what I see coming in the macroeconomic future than the general 60/40 traditional investment model that most people and funds tend to follow. I’ve been thinking about this portfolio model for a very long time, and we are putting the final touches on the project. While the investment model itself is relatively straightforward, all of the details involved with making sure that all of the regulatory i’s and business t’s are crossed – the stuff that has to happen behind the scenes – is far more complex.

The last few days have been like “old home week.” I had many more friends than I knew coming to Las Vegas for FreedomFest. Way too long a list to mention everyone, but I did get to sit down with Steve Forbes and Bill Bonner for a long coffee, talking about the “old days” of investment newsletter and magazine publishing – how things have changed over the last 35 years, and yet the principles of the business are generally the same. We just have to use ever-changing new methods to meet our objectives. I moderated a panel with Steve Forbes and Rob Arnott, which, if schedules permit, I will try to reproduce at my conference next year. And then I got to listen to George Gilder and spend a long lunch comparing notes on the roles of gold and Bitcoin and the actual mathematical basis for a new approach to economics. Heady stuff…

It is quite likely that a large fraction of my list does not know who Bill Bonner is. He may be the largest private publisher in the world. I asked him how many newsletters and magazines he now publishes, and he shrugged his shoulders and said, “More than a few hundred.” He started Agora back in the late ’70s and just kept growing, empowering other people to create and publish their own letters with his backing. In contrast to the normal top-down model of publishing, Bill is a venture capitalist of publications. He provides the backbone, but you have to eat your own cooking and create your own cash flow. He is now in over 13 countries and languages and probably delivers newsletters in every country in the world.

It is a long way from 1982, when I was also in the newsletter publishing business and Bill and I were doing enough together over the phone that I decided that this Texas country boy needed to travel to Baltimore to meet him. I flew into Baltimore, rented a car, and drove to his office. Younger readers have probably watched a show on HBO called The Wire. Believe me, what they depict on that show is an upgrade from where Bill’s offices were. He literally bought his office building for a dollar from the city (and now contends that he overpaid) in what was a very scary part of town. I remember parking a block away and actually being afraid to get out of the car to walk to his office. Remember, I was 32 years old and hadn’t been out of Texas very often. I was not your worldly wise, globetrotting, sophisticated, unafraid-to-walk-through-the-middle-of-riots-in-Africa raconteur that I am today. (Please note sarcasm, although I have walked into riots in Af rica. A story for another day.)

I finally worked up the courage to walk over to Bill’s office, knocked on the door, and heard about half a dozen bolts and latches being worked on the other side. Finally the door eased open a few inches, and an anxious young woman peered out at me. Probably noticing that I was more nervous than she was, she opened the door to let me in, then hurriedly closed the door and refixed all half-dozen latches. I walked up a few levels (this was a four-story row building) to an open-floor office where there were a dozen desks and people busily working amidst a mountain of files and papers strewn everywhere in what was clearly a filing system that only a group of ADD writers could appreciate.

Bill and I seemed to recognize the country boy in each other and hit it off, and we’ve been fast friends ever since. Thirty-four years later, Bill hasn’t changed all that much from the wrong-side-of-the-tobacco-farm guy from rural Maryland that he was back then – except for the missing hair. I travel from time to time to one of the homes he has scattered around the world. He has châteaus in France and haciendas in Argentina, beach homes in Nicaragua, etc. – it sounds more exotic than it really is. He grew up as an all-purpose fix-it guy, not unlike your humble analyst. He differs from me, however, in that he actually still likes to do all that hands-on stuff; so when he buys a château, what it really is, is a monstrous money pit where he tries to do as much of the fix-it work as he can with his own two hands. Ten or fifteen years later, he really has a nice place. And it was good training for his six kids, as he made them work durin g the summers, stripping paint, pulling wires, building stone walls, planting trees, and doing all the little things you have to do when you have a pile of rocks that once upon a time was a magnificent dwelling. Not exactly the life I would want to live if I were a gazillionaire, but good work if you can get it.

Bill may be the best storyteller that I know. That is different from being a good writer. Writers convey information. Storytellers may also convey information, but the package they put around the information is engaging and makes you think. A well-told story around the information allows you to internalize it more easily. We are genetically hardwired to appreciate a good story. We evolved from human beings who spent a lot of time around the campfire, swapping stories. Learning to live in groups and work together is a big part of why our species flourished, and it seems that people who enjoyed a good story survived and passed that predilection on to their descendants, over many thousands of generations.

When people ask me what I do, I tell them I’m a writer. But to tell the truth, I really want to be thought of as a storyteller. I guess I’ve always wanted to be Bill Bonner when I finally grow up – just without having to build stone walls with my bare hands.

You have a great week. Find a friend or two or three, take them to a long dinner, and spend the time telling stories. Everybody has a few stories. You will find they will help you survive as well.

Your storytelling wannabe analyst,

John Mauldin

subscribers@MauldinEconomics.com

| Digg This Article

-- Published: Monday, 18 July 2016 | E-Mail | Print | Source: GoldSeek.com