Crisis averted—for now. Last week President Donald Trump met for the first time with Chinese President Xi Jinping at his luxury Palm Beach estate Mar-a-Lago, where the two leaders discussed North Korea and trade, among other topics.

Several times before I’ve commented on the implications of a possible U.S.-China trade war in response to Trump’s repeated calls to raise tariffs on goods shipped in from the Asian giant. On the campaign trail, Trump threatened to name China a currency manipulator and even suggested that, were he to become president, he would serve Xi a “McDonald’s hamburger” instead of a big state dinner.

I’m happy to say that no Big Macs appeared to be on the menu last week. Nor were there any immediate signs of a disastrous trade war. In a much-needed win for Trump, the two leaders agreed on a 100-day assessment of the trade imbalance between the world’s two largest economies. In addition, Xi pledged to give the U.S. better market access to important Chinese industries such as financials and consumer staples. Specifically, he conceded to lift China’s ban on U.S. beef imports, in place since 2003.

Perhaps Trump is the master negotiator he’s always claimed to be.

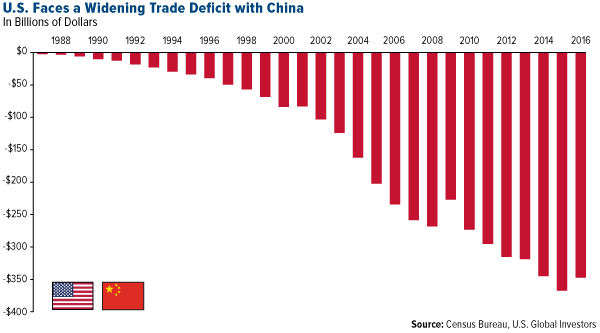

As encouraging as this news is, it will likely take a while before significant improvement can be made in balancing trade between the two nations. In 2016, the U.S. trade deficit with China stood at a staggering $347 billion, down from $367 billion in 2015.

China’s Importance as a Trading Partner Should Only Increase

My use of the word “crisis” above was not made lightly. China is currently America’s third-largest export market after Canada and Mexico, having bought $116 billion worth of U.S. merchandise in 2016. That’s up from $19 billion in 2001, an increase of 510 percent.

The U.S., in other words, really can’t afford a trade war with such an important trading partner.

On Tuesday, the president tweeted that China would get a “far better” deal with the U.S. “if they solve the North Korean problem.” But then, it’s the U.S. that’s seeking a better deal from the Chinese, not the other way around.

Among the most valuable U.S. exports to China are, in descending order, oilseeds and grains, aerospace products and parts, motor vehicles and electronic components such as semiconductors.

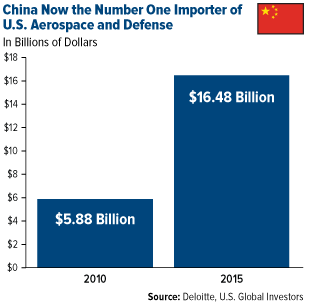

Since 2010, China has been the world’s top purchaser of light vehicles manufactured by General Motors, and today it’s an exploding market for aerospace and defense companies. Between 2010 and 2015, China surpassed Japan, the U.K., Canada and France to become the number one importer of U.S aerospace and defense equipment, according to Deloitte. The Asian country spent $16.48 billion on American-made civilian aircrafts, engines and aviation parts in 2015, up more than 180 percent from five years earlier.

Boeing is currently China’s leading provider of commercial jets. Back in September, the Chicago-based aerospace company announced that China was in need of more than 6,800 new aircrafts over the next 20 years, an ongoing enterprise valued at roughly $1 trillion.

So crucial is the Chinese market that Boeing, in cooperation with Chinese aerospace manufacturer Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC), just began construction on a Boeing 737 completion center in the island-city of Zhoushan. The center is Boeing’s first-ever overseas facility. By 2018, it should be capable of delivering as many as 100 737s per year.

Demand for health care goods and services is also set to expand dramatically as the country’s population ages. By 2030, an estimated 345 million Chinese will be over the age of 60, necessitating even more medicines, treatments and medical devices.

Once this 100-day assessment period ends, my hope is that the U.S. and China can continue to work on strengthening trade. China should continue to be a valuable partner as its gross domestic product (GDP) grows and its citizens’ incomes rise. As I shared with you in February, Morgan Stanley projects the country to become a high-income nation sometime between 2024 and 2027. Looking ahead, the Asian country could conceivably become America’s number one export market—provided Trump can hash out a better trade deal without inciting retaliatory trade blockades.