That’s it. It’s the final straw. One of the alternative investing newsletters had a headline that screamed, “Bitcoin Is About to Soar, But You Must Act by August 1 to Get In”. It was missing only the call to action “call 1-800-BIT-COIN now! That number again is 800 B.I.T..C.O.I.N.”

Is it about to go up? Maybe. We don’t know. And everyone should by now be skeptical of all “rocket to take off on XYZ date” claims. Between them, surely these newsletters have predicted thousands of the past zero blastoffs of gold and silver since 2011.

We have discussed bitcoin in the past, to argue that it is not money (a video here, and articles here and here). Bitcoin is not money because it is not a good. It’s just a number in a database. Money is a kind of good (genus). The most marketable kind (differentia).

Money must be a good because we are physical beings in a physical world and final payment—which is not demanded all the time, or even often—must be a physical thing that you can hold and touch in your physical hands. Bitcoin is not a physical good, so it represents, not final payment, but intermediate payment. It is not final until you trade the bitcoin for a real good. In the language of economics, a real good has utility apart from one’s hope to exchange it for something else. Bitcoin has no utility apart from this hope of its value in exchange, its price.

There is not one price but always two prices: bid and offer. When one has a thing and relies on someone else to buy it (or accept it in exchange), it is the bid price which is relevant. The offer price may be close above the bid, or it may be much higher. Typically sellers are reluctant to sell below their cost, but that has nothing to do with buyers. Buyers make a bid based on how they value it (or not).

This fact right here is sufficient to debunk the labor theory of value. Suppose producing a painting takes you 50 hours of labor plus $100 in materials. That does not matter. If your name is Banksy, people might be happy to pay tens of thousands of dollars for the painting. If your name is Keith Weiner, not so much (Keith is not known for having any skill at painting, though he can take some mean photographs).

For all commodities, for all real goods, for all tangible products, there is always a bid. Even a junk car is worth something to the scrap dealer. Even sand is worth something to the landscape contractor.

If a commodity is useful for something, it will have a robust bid. The price may be low or high, but the bid will be set by those who have a productive purpose in mind. If you can buy something, add a little bit of value from labor (e.g. cleaning it up) and sell it for $1,000 then you are willing to pay up to, say, $900.

Take copper. Copper can be used for wiring and plumbing (and many other things). If you manufacture plumbing, and you know that with a dollar worth of labor you can turn copper into a pipe that sells for $3.75, what are you willing to pay for the copper? Perhaps you would go up to $2.50 (it’s now about $2.85). If the price of copper drops, this new buyer will come into the market (for now, plumbing is made of plastic).

In this light, we now get to the 64 billion dollar question. What is the bid on bitcoin? What is it useful for, and who would buy it for that purpose?

Right now, bitcoin is a lot of fun. Its price is being driven up by frenzied speculators. With each new price level, proponents become bolder and more aggressive. Bitcoin will replace the dollar, bitcoin will go up to $1,000,000, the dollar is failing, get yours before August 1, etc. Many of these arguments were popular when the price of gold was rising relentlessly up through 2011.

But what’s the ultimate bid? Where is the floor, where it cannot go below because it’s just too profitable to buy it, transform it into a higher-value good to sell at a profit? Where is the floor where individuals will buy more and more because they want bitcoin in their living room, or in the tank of the car, or in their refrigerator, or in their basement?

It doesn’t exist, does it?

This is not a prediction for tomorrow morning. Indeed timing these things is impossible. However, there will come a point when the speculators turn. Perhaps their collective thumbs will move the planchette on the price-chart Ouija board to paint an ugly chart pattern (much uglier than head-and-shoulders). Whatever its initial cause, what will happen is clear in light of the above discussion.

The price of bitcoin could drop to any level. Incidentally, bitcoin could be used in exchange as it is now, whether its price is $0.01 or $1,000,000.

People often say that bitcoin is like gold, or even say it is “digital gold”. They are just trying to cash in on gold’s good name. The problem of the bid is another key difference between bitcoin and gold. Gold is an extremely useful commodity. Bitcoin is not any kind of commodity at all. It does not have a real bid at all, only the ever-changing bid of the fickle speculator.

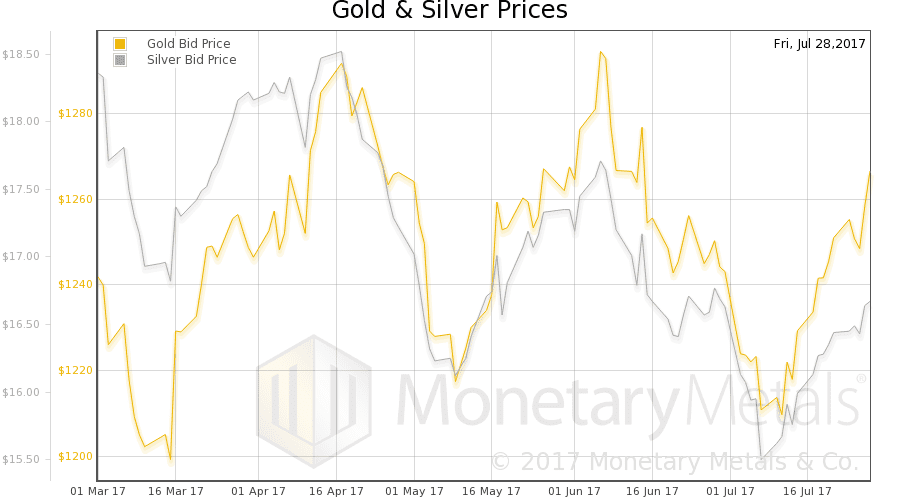

The prices of the metals rose some more this week, with gold +$13 and silver +$0.24. However, that leads to the question: is it speculators getting ahead of the fundamentals, or is it real?

Three weeks ago, with the price of gold $56 lower and the price of silver $1.15 lower than today, we asked if that was capitulation. We cited some circumstantial evidence (plus a rising scarcity of both metals as measured by the cobasis). We did not call for a moonshot, but a “normal trading bounce within the range.”

Today it is time to ask if the bounce is down, and if now is the time for a normal correction. And if it’s the same answer for both metals.

We will show graphs of the true measure of the fundamentals. But first charts of their prices and the gold-silver ratio.

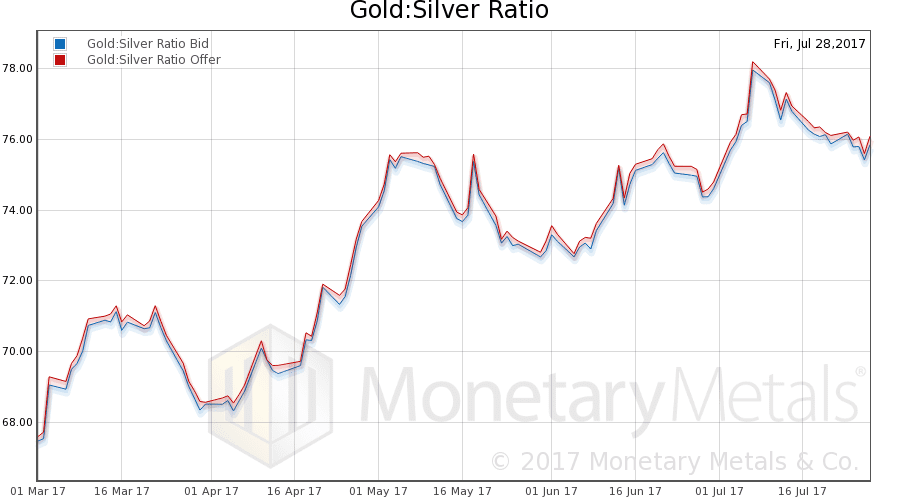

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio. The ratio moved down slightly this week. We find it interesting that the ratio did not fall farther.

In this graph, we show both bid and offer prices for the gold-silver ratio. If you were to sell gold on the bid and buy silver at the ask, that is the lower bid price. Conversely, if you sold silver on the bid and bought gold at the offer, that is the higher offer price.

For each metal, we will look at a graph of the basis and cobasis overlaid with the price of the dollar in terms of the respective metal. It will make it easier to provide brief commentary. The dollar will be represented in green, the basis in blue and cobasis in red.

Here is the gold graph.

The dollar fell again this week (the mirror image of the rising price of gold). As the dollar fell, the cobasis increased—gold became more scarce.

Rising price + rising scarcity = rising fundamental price (fundamental price chart here).

Now let’s look at silver.

In silver, unlike in gold, as the dollar has dropped (i.e. the price of silver measured in dollars has risen), the metal has become more abundant.

Our calculated silver fundamental fell about 50 cents this week, or about 75 cents in the past few weeks. So while the price of gold may continue to rise to perhaps over $1,300 the price of silver could be a bit weaker. We calculate a fundamental gold-silver ratio of about 79 (chart here).

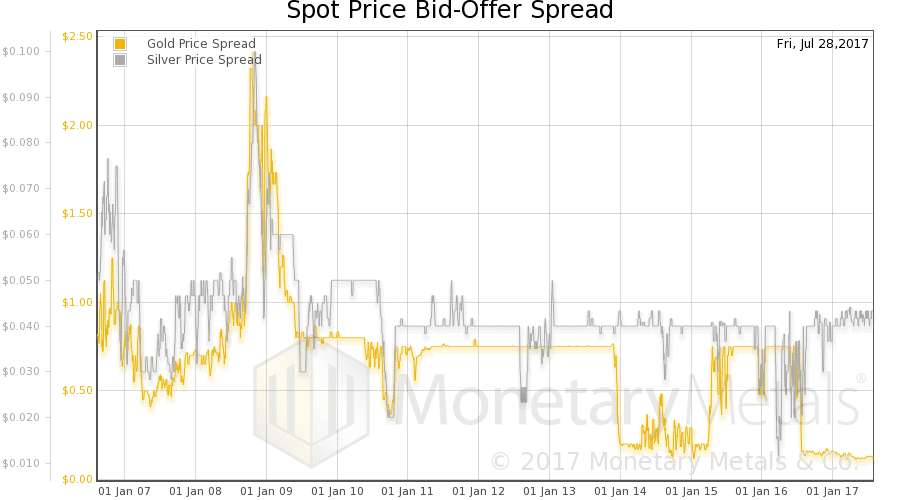

Coming back to the bid-ask spread, we thought we would publish another chart off our website. This one shows the bid-ask spread of spot gold and spot silver.

There are two salient features. First, note that the spread is really tight in both metals (though while the spread in gold dropped in mid-2016, in silver it increased). It is currently around 12 cents in gold. An ounce of gold is over $1,200 and the difference between bid and ask is $0.12 or 0.01 percent! In silver, it is around 4.2 cents, or 0.25 percent. Gold is more liquid, much more liquid.

Second, when the financial system buckled and nearly collapsed in 2008, the spreads widened to $2.40 and $0.10 in gold and silver, or 0.33 percent and 1.05% respectively. Compared to real estate in a normal market, both metals are extremely tight. Compared to illiquid assets during the peak of the crisis, it’s incredible. We recall a story of a guy who bought a famous painting by old master during the top in 2007. He paid, as we now recall, around $13 million. During the crisis, he was forced to sell it. He got $100,000. We assume the offer price on such a painting would still be $10 million or more. But $100,000 was the bid.

© 2017 Monetary Metals