-- Published: Tuesday, 4 June 2019 | Print | Disqus

By: Keith Weiner, Monetary Metals

We have been discussing the impossibility of China nuking the Treasury bond market. We covered a list of challenges China would face. Then last week we showed that there cannot be such a thing as a bond vigilante in an irredeemable currency. Now we want to explore a different path to the same conclusion that China cannot nuke the Treasury bond market.

To review something we have said many times, the dollar is borrowed. It is not printed. Every time fresh new dollars are created, there is a borrower. There is never a giftee. The borrower has the dollar as an assetóbut he also has a matching liability.

Once we understand that the balance sheet has assets and liabilities, it is senseless to talk about the increase in quantity of the asset side without addressing the liabilities. In familiar monetary economics terms, the asset is supply. However, there is a liability too. That liability represents demand. Perpetual demand. Letís look at this.

Example: a farmer borrows to buy more land. The price of land is high (as weíre in an environment of uber-low interest, and asset prices move inverse to rates). So to buy it, he must incur many dollars of debt. And he needs great revenue to service that debt. This is because the gross revenue does not service debt. Only the net profit can be paid out as interest or principal.

Our farmer would be lucky if a few pennies of each dollar of revenue are free cash flow, net of all expenses. Therefore his demand for dollars of revenue is many multiples of the debt service payment. This demand, letís not forget, is ongoing for so long as he has the debt.

How many multiples?

By a process of arbitrage, profit margins are brought down to the interest rate (in a free market, i.e. gold standard, interest would be pushed up too). Suppose one could make 10% return on capital in the farming business. If the interest rate is 1%, itís a great opportunity. Farmers will keep borrowing to expand, until they bring the return down. They wonít push it all the way to the interest rate, but they will go pretty far in that direction.

If the interest rate is 4%, then every borrowed dollar incurs 4 cents of interest every year. If the return on capital is 5%, then every dollar of capitalóweíll assume itís all debt to keep the math simpleóis generating 5 cents of profit. There is not necessarily a simple or linear relationship between return on capital and profit margin. But we can certainly say that as return on capital is pushed down, so is the profit margin.

In this example, 80% of the return on capital goes to debt service (4 out of 5). Only 20% is used to generate profits after interest expense.

Only 20 cents of capital is uses to generate profits after interest expense. To keep the math very simple, suppose the profit margin matched the return on capital. 5%. Then the farmer must generate 80 cents of revenue for every dollar of debt. Or else. Or else what? The lenders will repossess his farm, and he will lose his livelihood not to mention his life savings and likely his multigenerational legacy.

The farmer must do whatever it takes to grow enough wheat to generate these revenues. And all of the other wheat farmers are doing the same.

Their demand for dollars impels them to a relentless urgency. They must dump as much wheat as it takes on the market. This wheat goes onto the bid price, thus pressing it lower.

Farmers must generate nearly as much annual revenue as they have debt (in our example). And the same for all low-margin commodity producers.

And then the interest rate is lowered again (gotta boost GDP, donítchíknow?) And the next marginal farmer borrows to narrow the new gap between interest and return on capital. The farmers (and indeed all capital-intensive businesses) are put on a treadmill, while the Fed keeps turning up the speed.

More importantly, we can see the mechanism by which borrowing dollars creates perpetual demand for dollars. To say it againóitís that importantódebtors must generate, every year, almost as many dollars of revenue as they owe in debt.

And it is perpetual. Debt cannot be extinguished. One debtor may get out of debt. At least in theory. Although our hapless farmer cannot. He canít outrun that treadmill. But if a business does manage to pay off its debt, it is simply shifting the debt to another party. Without gold in the monetary system, there is no final payment. There is no mechanism to make a debt go out of existence.

Those who look only at the newly-created quantity of dollars are missing the newly-created perpetual liability. And to say money is ďprintedĒ explicitly denies the liability. There is no helicopter drop of free money. There is only the deceptively cheap rate to borrow. Deceptive, because itís hard and getting harder to earn enough to pay the vigorish. Counterintuitively, the lower the prevailing rate the harder it becomes. It would be one thing if you and only you had access to borrow at a special low rate. But thatís not the case. Everyone is borrowing at that low rate, too.

And to make matters worse, letís tie this into the theme we developed prior to Chinaís nuclear option. Useless ingredients added by regulators. Every time government forces the farmer (or the miller, the baker, or the grocer) to add useless ingredients, it pushes costs up. But this does not help the farmer catch his breath on the treadmill. Quite the contrary, it is like shoving a burden of useless stuff into his backpack. The farmerís only relief is the bankruptcy of his competitors, but so long as the interest rate keeps falling there will always be more new competitors.

It is not faith that holds up the value dollar. It is not awaiting one revelation (e.g. Fed audit) away from sudden collapse. Its value is no illusion to be so easily dispelled. Its value comes from the struggles of the debtors. For example, our farmer working harder and harder to produce more wheat. Which he is obliged to sell, at cheaper and cheaper prices.

Most people regard a currencyís value as 1/P (the general price level). Which means every farmer and indeed every debtor is working to increase the value of the dollar, as the Fed works to lower its interest rate.

We went on this seeming diversion, because it is important at this point in our development of the ideas around China and US interest rates, to see that an increase in the quantity of currency will not necessarily cause prices to rise. In a falling rates environment, it will lead to the opposite. As we have seen, in wheat more clearly than in other prices.

So what does this have to do with the price of tea in China (OK, OK, we could not resist so many good opportunities wrapped into one)? Stay tuned for Part IV next week!

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

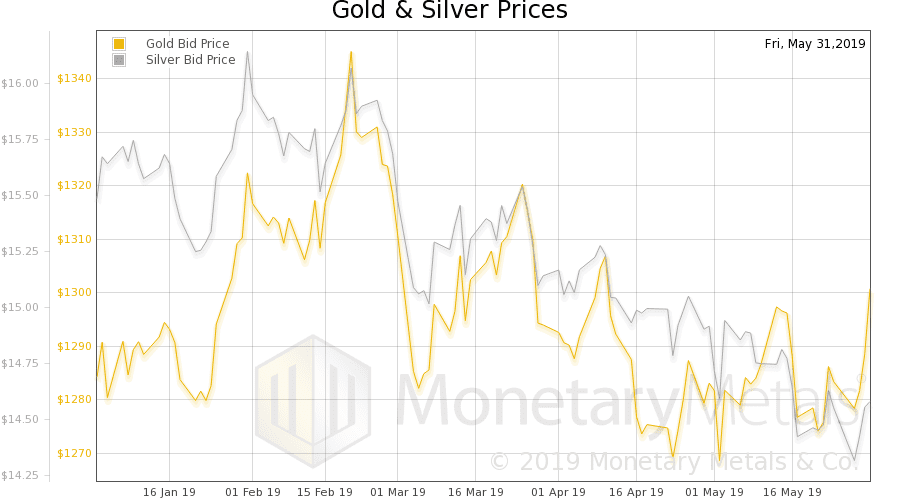

The price of gold jumped a whole twenty bucks. We imagine that the marginal gold bug is relieved to be rid of his gold, in this opportunity afforded by the highest price since early April. Ok, all kidding aside, the price of silver went up a penny.

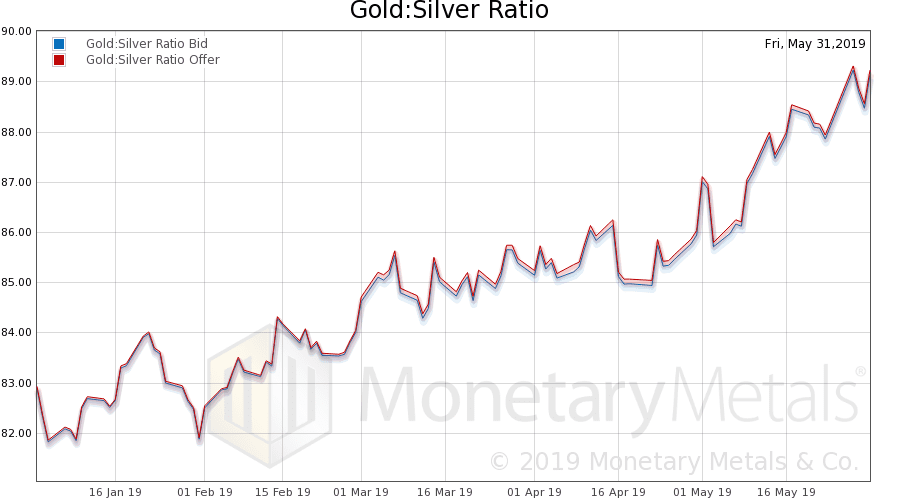

We now have a new high in the gold-silver ratio. This can keep going up forever, right? The silver bugs donít mean to imply that silver is being demonetized. However, when they say that silver has been in deficit for decades, they mean the stocks are being consumed. If that were true, it would mean that silverís stocks-to-flows ratio is moving towards that of any non-monetary commodityís ratio. Such as oil or copper.

Is it really true?

Some forces would tend to push in that direction. Digital gold accounts allow for small fractions of an ounce, thus solving one of the problems solved by silver. Small gold units like the Aurum, available down to 0.1 gram sizes, also solve the problem.

We donít think either of these eliminates the need for silver. Digital accounts are, well, digital. They do not solve the need to have the metal in hand. To redeem it, and take it home. Aurum, apart from not being ubiquitous to 7 billion people, also has a greater bid-ask spread.

For the wage earner, setting aside 10% of his weekly wage, silver is the most marketable commodity in the smallói.e. the most hoardable. If one is making $500 a week, 10% is about four silver 1-ounce coins or rounds. They heft nicely in the hand, and the frictional cost to get into and out of precious metal is lower than for gold of that value.

There is much current discussion of whether or not there is rising inequality, a growing gap between the capitalist and the worker. The Left is pushing this idea, because it supports their a priori conclusion: to tax the #$*&%! out of the rich. To equalize them. The Right says no, poor people have iPhones and Netflix (in the US) or at least ample food in the rest of the world. The Right seeks to head the Left off at the pass. They think to deny the observation and hence avoid the prescription.

Readers know that we blame the Fed and its falling interest rate, for rising (paper) value of assets and downward pressure on wages. In economics terms, each drop in the interest rate causes an increase in the marginal productivity of labor. Not an increase in productivity. The margin goes up, i.e. the hurdle.

We have an interesting data point in the rising gold-silver ratio. Those who would set aside some of their wages to buy silver are under pressure. There is less pressure on gold, whose buyers include many non-wage-earners.

Anyways, letís look at the supply and demand picture of gold. But, first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). The ratio rose, to a new high over 89.

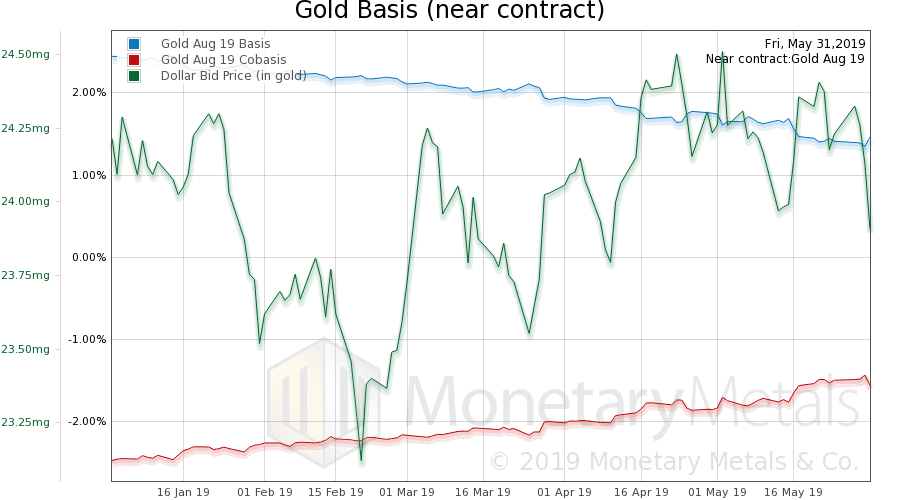

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

Big drop in the dollar (inverse of the rise in the price of gold, in dollars). Not so much change apparent in the scarcity (i.e. cobasis). The gold basis continuous a bit of a move.

The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price was unchanged at $1,372.

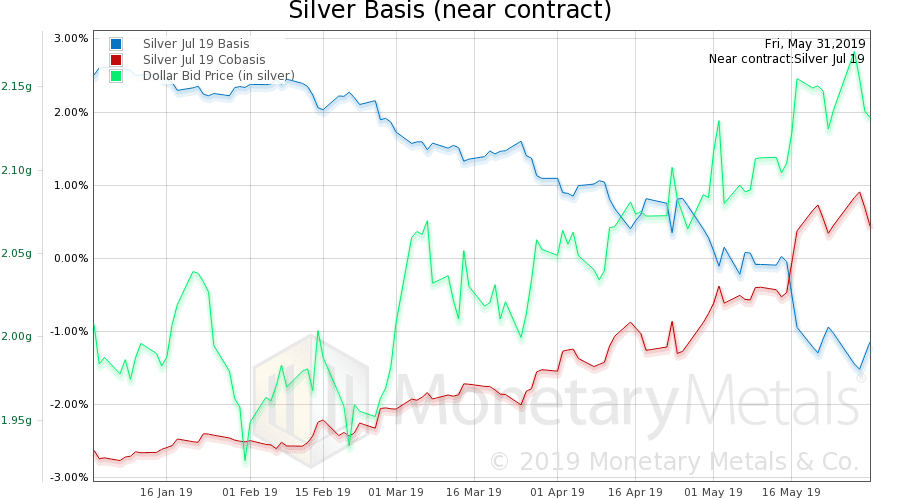

Now letís look at silver.

Silveróboth price and scarcityóis more volatile. And itís easy to see the changes in the cobasis that correlate nicely with the changes in the price (of the dollar, measured in silver). When silver sells off, itís futures. And when silver is bought up, itís futures. Predominantly.

The Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price was up a bit, to $15.46.

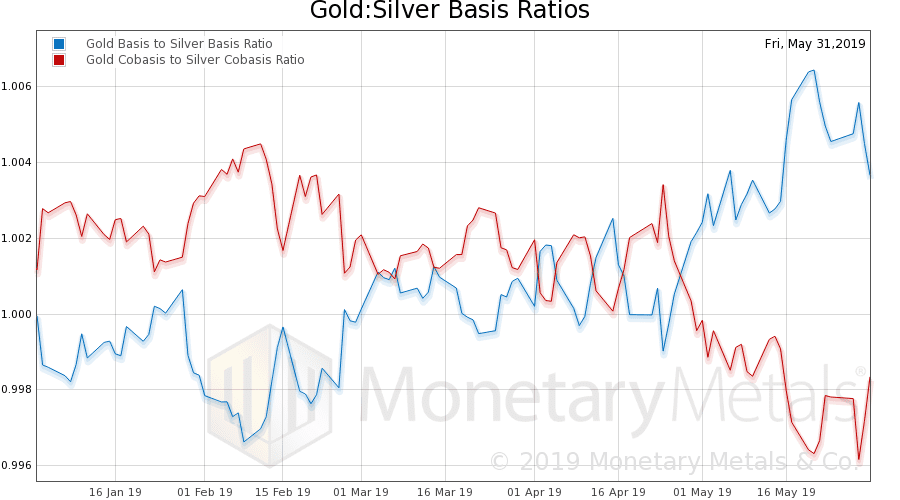

Letís look at the gold-silver ratio. Not the price of it, which as we noted above was over 89. The ratios of the gold basis to silver basis. And gold cobasis to silver cobasis.

The ratio of the bases has come in a bit, but it is still right around the maximum achieved in the last few years. A higher ratio of the bases suggests that silver is likely to outperform gold.

This bears watching.

© 2019 Monetary Metals

| Digg This Article

-- Published: Tuesday, 4 June 2019 | E-Mail | Print | Source: GoldSeek.com