-- Published: Monday, 1 April 2019 | Print | Disqus

Cracks Appearing

First Domino

Constrained Hiring

Tariff Trouble

A Virtual Pass to the SIC

RIP, Andrew Marshall, The Last Warrior

Cleveland, Chicago, Dallas, Austin, Dallas, and Back Home to Puerto Rico

This month, the Federal Reserve joined its global peers by turning decisively dovish. Jerome Powell and friends haven’t just stopped tightening. Soon they will begin actively easing by reinvesting the Fed’s maturing mortgage bonds into Treasury securities. It’s not exactly “Quantitative Easing I, II, and III,” but it will have some of the same effects.

Why are they doing this? One theory, which I admit possibly plausible, was that Powell simply caved to Wall Street pressure. The rate hikes and QT were hitting asset prices and liquidity, much to the detriment of bankers and others to whom the Fed pays keen attention. But that doesn’t truly square with his 2018 speeches and actions. The Fed’s March 20 announcement suggests more is happening.

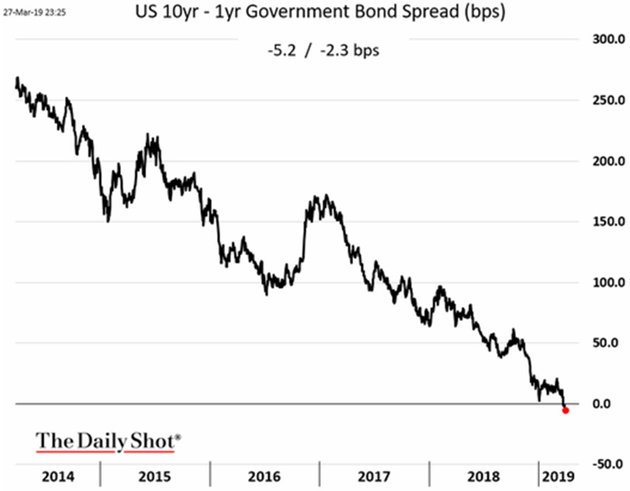

I think two other factors are driving the Fed’s thinking. One is increasing recognition of the same slowing global growth that made other central banks turn dovish in recent months. The other is the Fed’s realization that its previous course risked inverting the yield curve, which was violently turning against its fourth-quarter expectations and possibly toward recession (see chart below, courtesy of WSJ’s “Daily Shot”). That would not have looked good in the history books, hence the backtracking.

On the second point… too late. The yield curve inverted, and recession forecasts became suddenly de rigueur among the same financial punditry that was wildly bullish just weeks ago.

My own position has been consistent: Recession is approaching but not just yet. Yet like the Fed, I am data-dependent and the latest data are not encouraging. Today, we’ll examine this and consider what may have changed.

Let’s start with a step back. The global economy clearly hasn’t recovered from the last recession like it did in previous cycles. Yes, the stock market performed well. So has real estate. We’ve seen some economic growth, which in a few places you might even call a “boom,” but for the most part it’s been pretty mild. Unemployment is low, but wage growth has been sluggish at best. Rising asset prices, fueled by almost a decade of easy monetary policy, also contributed to wealth and income inequality, which fueled populist and now semi-socialist movements around the world.

This slow recovery began fading in the last few quarters. The first cracks appeared overseas, leaving the US as an island of stability. Not coincidentally, we also had (slightly) positive interest rates and thus attracted capital from elsewhere. This let our growth continue longer. But now, signs of weakness are mounting here, too.

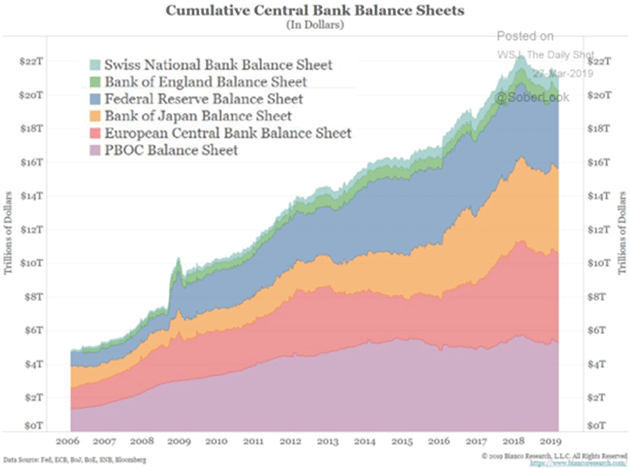

Recall, this follows years of astonishing, amazing, unprecedented, and astronomically huge monetary stimulus by the Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan, European Central Bank, and others. In various and sundry ways, they opened the spigots and left them running full speed for almost a decade. And all it produced was the above-mentioned weak recovery. (Chart below from my friend Jim Bianco, again via “The Daily Shot”)

That, alone, should tell you that putting your faith in central bankers is probably a mistake. We can’t know how much worse the last decade would have been without their “help,” but does this feel like success?

Yet here we are, with millions still in the hole from the last recession and another one possibly looming. We also can’t rely on historical precedent to identify where, when, or why it will start. But we can make some educated guesses.

Earlier, I called the US an “island of stability.” Other such islands exist, too, and Australia is high on the list. The last Down Under recession was 27—yes, 27—years ago in 1991. No other developed economy can say the same.

The long streak has a lot to do with being one of China’s top raw material suppliers during that country’s historic boom. But Australia has done other things right, too. Alas, all good things come to an end. While not officially in recession yet, Australia’s growth is slowing. University of New South Wales professor Richard Holden says it is in “effective recession” with per-capita GDP having declined in both Q3 and Q4 of 2018.

(By the way, Italy is similarly in a “technical recession.” Expect more such euphemisms as governments try to avoid uttering the “R-word.”)

As often happens, real estate is involved. Australia’s housing boom/bubble could unravel badly. Last week, Grant Williams highlighted a video by economist John Adams, Digital Finance Analytics founder Martin North, and Irish financial adviser Eddie Hobbs, who say Australia’s economy looks increasingly like Ireland’s just before the 2007 housing collapse.

The parallels are a bit spooky.

Australia’s household debt to GDP was 120.5 per cent as of September last year, according to the Bank for International Settlements, one of the highest in the world. In 2007, Ireland was sitting at around 100 per cent.

At the same time, the RBA puts Australia’s household debt to disposable income at 188.6 per cent. Ireland was 200 per cent in 2007, while the US was only 116.3 per cent at the start of 2008.

RBA figures also show more than two thirds of the country’s net household wealth is invested in real estate. In 2008, that figure was 83 per cent in Ireland and 48 per cent in the US. Meanwhile, 60 per cent of all lending by Australian financial institutions is in the property sector.

In 2007, the International Monetary Fund gave the Irish economy and banking system a clean bill of health and suggested that a “soft landing” was the most likely outcome. Last month, the IMF said Australia’s property market was heading for a “soft landing”.

House prices in Sydney and Melbourne have fallen nearly 14 per cent and 10 per cent from their respective peaks in July and November 2017, coinciding with sharp drop-off in credit flowing into the housing sector both for owner-occupiers and investors.

Real estate is, by nature, credit-driven. Few people pay cash for land, homes, or commercial properties. So when credit dries up, so does demand for those assets. Falling demand means lower prices, which is bad when you are highly leveraged. It gets worse from there as the banking system gets dragged into the fray. Losses can quickly spread as defaults affect lenders far from the source.

This is not only an Australian problem. Similar slowdowns are unfolding in New Zealand, Canada, Europe, and China. It’s a global problem, and one company reveals the impact.

Shipping and transport stocks are kind of a “canary in the coal mine” because they are among the first to signal slowing growth. Last week, FedEx reported its international shipping revenue was down and cut its full-year earnings guidance. Its CFO blamed the economy, reported CNBC.

Slowing international macroeconomic conditions and weaker global trade growth trends continue, as seen in the year-over-year decline in our FedEx Express international revenue,” Alan B. Graf, Jr., FedEx Corp. executive vice president and chief financial officer, said in statement.

Despite a strong U.S. economy, FedEx said its international business weakened during the second quarter, especially in Europe. FedEx Express international was down due primarily to higher growth in lower-yielding services and lower weights per shipment, Graf said.

To compensate for lower revenue, Graf said FedEx began a voluntary employee buyout program and constrained hiring. It is also “limiting discretionary spending” and is reviewing additional actions.

FedEx shares have dropped roughly 27 percent in the past year, lagging the XLI industrial ETF’s 1 percent decline.

This little snippet overflows with implications. Let’s unpack some of them.

Revenue fell due to “higher growth in lower-yielding services.” So those who ship international packages have decided lower costs outweigh speed. Likewise, “lower weights per shipment” signals they are shipping only what they must, when they must.

FedEx is responding with an employee buyout program and “constrained hiring.” The company is overstaffed for its present requirements. This might also reflect increased automation of work once done by humans. In any case, it won’t help the employment stats.

In addition, FedEx is “limiting discretionary spending.” I’m not sure what that means. Every business always limits discretionary spending, or it doesn’t stay in business long. If FedEx is taking additional steps, then whoever would have received that spending will also see lower revenues. They might have to “constrain hiring,” too.

Obviously, FedEx is just one company, although a large and critically positioned one. But statements like this add up to recession if they grow more common… and they are.

One reason FedEx is in the vanguard is that it’s uniquely exposed to world trade, the growth of which is diminishing for multiple reasons.

Part of it is technology. The things we “ship” internationally are increasingly digital, and they travel via wires and satellite links instead of ships and planes. These sorts of goods aren’t easily valued for inclusion in the trade stats.

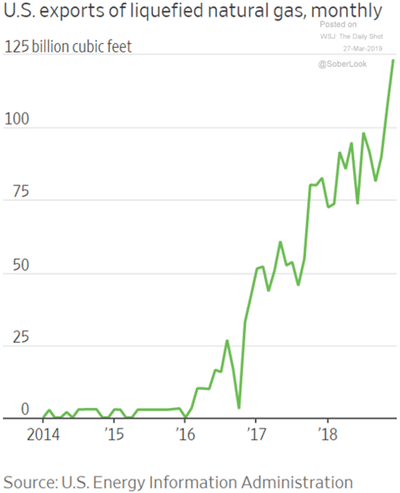

Energy is another factor. Between US shale production and renewable energy sources, we don’t import as much oil and gas from across the seas as we otherwise would. That shows up in both trade and currency values. The US dollar is stronger now, in part because we send fewer dollars to OPEC.

Note the massive (and stealthy!) growth in LNG (liquified natural gas) exports in the past few years. Think what this will look like in a few years, with not one but four LNG export terminals on the US coasts. Natural gas is also the basis for much of the chemical and fertilizer industry. Abundant US supplies (and prices less than half the cost of Russian gas in Germany) help many US industries compete.

Those are just signs of normal progress and change. The economy can adapt to them. The greater threat is artificially constrained international trade, which is what the Trump administration’s trade war is creating.

Last year, I explained how trade wars can spark recession and trade deficits are nothing to fear. I won’t repeat all that here. But we have since seen several market swoons/rallies as harsher trade restrictions looked more/less likely. Whether you like it or not, asset values depend on the (relatively) free flow of goods and services across international borders. Interfere with that and all kinds of assets become less valuable.

Starting a trade war, at the same time growth is slowing for other reasons, is more than a little unwise. Agricultural tariffs have already ripped through US farm country to devastating effect, leaving losses some farmers may never recover.

The president’s tariff threats had other impact as well. Companies raced to import foreign-supplied components and inventory before the tariffs took effect. This jammed ports and highways last year, not with new demand but futuredemand shifted forward in time.

This is important, and I think we will see the impact soon (if we are not already). Transport and logistics companies geared up for last year’s surge, expanding their facilities and hiring new workers. Importers built up inventory in an effort to avoid tariffs that were supposed to take effect in January. The deadline was extended, but the threat is still alive.

At some point, all this has to stop. Carrying inventory is expensive and will eventually outweigh the benefit of avoiding tariffs. Then the boom will come to a screeching halt. Imports will fall as companies work down inventory. All those jobs and construction projects will disappear.

That, combined with the other cyclical factors and high debt loads everywhere, could easily add up to a recession. Exactly when is hard to say. Recessions usually get pronounced in hindsight, so there’s some possibility we are in one right now. But I still think we’ll avoid it this year. Getting into this box took a long time and so will getting out of it.

Regardless, we’ll have a recession at some point. I think the next subprime crisis will be in corporate debt. Next week, we’ll look deeper into the timing question, what the yield curve tells us, and why the next decade will bring little or no economic growth.

I realize this is not a happy conclusion, but I call them as I see them. I’ll leave you with one final but critically important thought: Prepare, don’t despair. Tough times are coming but we can handle them. You have a chance to get ready. I highly suggest you take it.

Time flies. Monday is already April Fool’s Day, and the Strategic Investment Conference is only a month and a half away. I’m really looking forward to this year’s SIC—the lineup of speakers is truly phenomenal.

Some of them confirmed they were coming at the last minute, like my old friend Kyle Bass who enriches and energizes every conference he speaks at. I can’t wait to hear what he’ll talk about on our China panel.

The SIC is completely sold out at this point... but you can still attend “virtually.”

Like last year, we’re offering our Virtual Pass at a steep pre-SIC discount. Thanks to the live stream feature—a huge hit with passholders in 2018 when we introduced it—you will be able to watch most of the conference live, as it happens.

You’ll even be able to ask questions and vote on the best questions for the speakers and panelists to answer. It’s the next best thing to actually being there.

And after the SIC is over, you will receive video and audio recordings, slide shows, and transcripts to enjoy at your leisure on your smartphone, tablet, or computer... again and again.

You’ll find all the details on this page. I hope you’ll decide to join us at the SIC via your Virtual Pass.

Andy Marshall, who for the last 50 years has often been called the most important strategic thinker you’ve never heard of, quietly passed away last Tuesday at age 97. Starting at the RAND think tank in 1949, he was persuaded to move from California by Henry Kissinger, who wanted his intellect at the White House National Security Council. In 1973, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger (with whom he worked at RAND) brought him over to the Defense Department to set up the enigmatically titled “Office of Net Assessment.” It was basically a think tank designed to analyze long-term threats and problems and help shape military strategy to deal with them. He was reappointed by every president and defense secretary until his retirement in 2014 at the age of 94.

In the 1970s, Andy famously contradicted the CIA and the foreign policy establishment about the strength of Russia’s economy and predicted its collapse. In the 1990s, he quietly circulated his first memo saying China should become the main strategic focus of the US military. Like his Russia analysis, it was ignored at first.

Called “Yoda” within the military establishment, Andy’s influence was enormous. I first met him over 10 years ago as he hosted small gatherings of economists and strategists to talk about their views of the future. I would find myself sitting at the table with names you would easily recognize, but for some reason he kept asking me back. He invited me to two of his famous week-long sessions at the Naval War College, where he would mix an eclectic group of thinkers with high-ranking military professionals to consider alternative futures. He asked questions and then put us in a room for 12 hours a day, plus long dinners afterward, to discuss the opportunities and problems the scenarios might entail. It was personally exhilarating and foundational for me.

At his retirement party, a former vice president, multiple defense secretaries, abundant military brass, and strategists gathered to honor this singular man’s 40+ years of continuous government service. He spent 65 years focused on keeping our military prepared for the future. I don’t have enough room to properly pay tribute to one of the great futurists of our times. Andy brought the model of competitive thinking that he learned at the University of Chicago to military strategy. He basically invented the arena of inferential analysis.

You can read much better reviews of Andy’s career here by his biographer (How is Yoda?) and at the New York Times and Washington Post. His life was chronicled in his biography, The Last Warrior: Andrew Marshall and the Shaping of Modern American Defense Strategy.

Just a few weeks ago, Andy again invited me to his apartment near the Pentagon, crammed full of books and journals, to meet with other analysts. Andy was still mentally vigorous and primarily focused on China. There, in his room, the “net assessment” of the potential problems with China were not sanguine.

I once asked Andy why he kept inviting me back to his meetings and forums. I truly had no idea. Every time I was in a room with him and the others he gathered, I felt well out of my league. He smiled and said, “Because you don’t think like other economists.” Coming from Andy, that may be the finest and greatest compliment I have ever received. Andy Marshall, requiescat in pace.

Starting Sunday, I will basically spend the night in each of the above cities before returning to Puerto Rico. In Cleveland, we will check my eyes, but I can tell you the surgery went very well. I have some last-minute meetings in Chicago (technically Wisconsin), then overnight in Dallas before I fly to Austin, and then Dallas for presentations. Click here for more information and to register.

I have been on the road too much this year, but other than the SIC in mid-May, my travel schedule looks rather tame for a few months. We’ll see…

Have a great week! Think of a friend or two who you really need to connect with. And then make it happen.

Your thinking about possible futures and my own net assessment analyst,

| John Mauldin

Chairman, Mauldin Economics |