-- Published: Sunday, 30 June 2019 | Print | Disqus

Comparative National Emergencies

What Happens if There Is a Recession?

On-Budget Versus Off-Budget Deficits

Forget Turning Japanese, We Are Turning Greek

Where Will the Money Come From?

Boston, New York, Puerto Rico, New York, Maine, and Montana

This week is the fourth in a series of five open letters responding to a series of essays by Ray Dalio, the founder of Bridgewater Associates. His original letters are Why and How Capitalism Needs to Be Reformed, Parts 1 and 2 and It’s Time to Look More Carefully at ‘Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)’ and ‘Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)’. My replies are here, here, and here. Today I continue my response.

I was quite pleasantly surprised to read a very generous and gentlemanly reply from Ray in Forbes last week, in which he clarified some of my understanding of what he wrote. I encourage you to read it after this letter for more context. I’ll continue responding to his original material but first a short piece responding to his letter in Forbes.

Dear Ray,

I want to thank you for your thoughtful and courteous reply to my first three essays. It was remarkably civil and I learned a great deal. Clearly you and I agree more than we disagree. Many of our differences are an emphasis on a different syllable in a word rather than the word itself. Much like tomato and to-mah-toe. I will continue my series in the spirit in which you replied, noting that my misunderstandings would have been cleared up in a few minutes in a normal conversation rather than a public internet back-and-forth. Part of the times we live in…

I will encourage my readers who are following this discourse to read your response, as there is much to be learned in your explanations of the nuances of MP3 and MMT. I somewhat conflated them in my first few readings of your letter, and your clarification helps immensely. I believe my fifth and hopefully last letter in this series next week will offer an alternative to this path we both agree would be perilous. These paragraphs from your response are at the crux of the matter:

Having studied these dilemmas in the past and thought a lot about the cause/effect relationships that determine how they work, it is my conclusion that central banks will have to turn to what I call Monetary Policy 3 (MP3) in the next downturn. MP3 follows Monetary Policy 1 (which is interest-rate-driven monetary policy), which continues until interest rate cuts can’t be big enough to do the trick. That’s when Monetary Policy 2 (which is central bank printing of money and buying financial assets) happens and continues until that doesn’t work anymore either. MP3 is fiscal and monetary policy working together with fiscal policy producing deficits that are monetized by the central bank. Modern Monetary Theory as it’s described is simply one version of many types of MP3. What I’m saying is that I believe that in the next downturn you will either see some form of MP3 from central banks or you will have terrible economic and social conditions.

To be clear, I’m not saying that such policies don’t have some undesirable consequences, and I don’t think that MMT is the best form of MP3. What I’m saying is that MP3 is the best of the bad alternatives and some form of it will likely happen, so one had better know how it works and how to deal with it. I welcome alternative descriptions of what will happen when both interest rate cuts and QE don’t work to stimulate the economy in the next significant downturn.

I quite agree that unless something is done there will be terrible economic and social conditions. As you say, we will have to choose between bad and perhaps even worse choices, none of which will be easy. The longer we wait, the more difficult and limited the choices will be.

I’m looking forward to hearing what form of MP3 will be best (or least bad). I quite agree that more QE will have its own attendant complications, creating the same problems as last time. The image of Christopher Walken demanding More Cowbellcomes to mind. More QE may be far more annoying, if not destructive.

I look forward to continued conversation…

John

(continuing from last week…)

While I am unsure wealth and income disparities, as obvious and politically charged as they are, rise to the level of a national emergency, I wholeheartedly agree that when 53-54% of America votes as if they are, politicians will agree it is a national emergency and do something, at a not insignificant cost. The resulting new debt could indeed spark a national emergency.

Let’s first look at this using historical data and Congressional Budget Office projections, which presume steady (though mild) growth and no recessions. Then we’ll tweak that data to see what happens if there is a recession at some point.

As noted above, the one seemingly bipartisan point of agreement is to never, ever discuss deficits in any serious manner. By “serious,” I mean actually suggesting specific solutions that would bring either higher taxes, lower spending, or both. Simply noting the debt exists, while important, isn’t serious discussion.

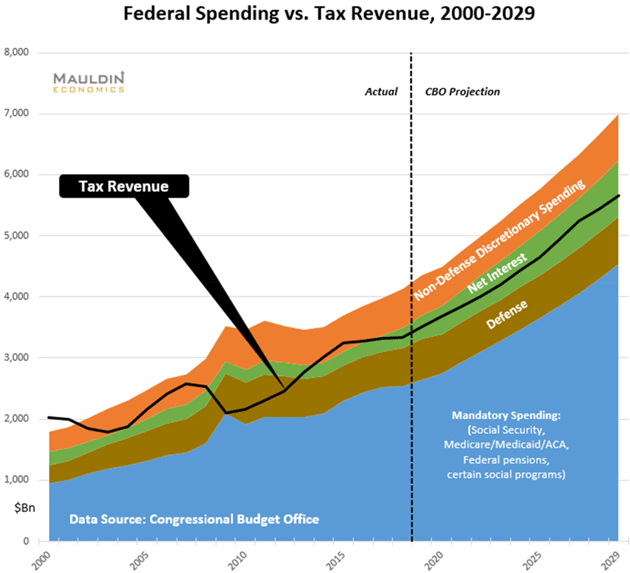

My associate Patrick Watson spent much of this week searching government websites to produce the charts and tables below. Let’s run through these to set up later discussions.

This first chart simply aggregates CBO spending and revenue figures. The CBO, of course, can’t predict a recession in the future and uses what it thinks are “best practice” projections. Note that tax revenue (the black line) is not enough to pay for mandatory spending, defense, and all of the net interest. Again, this is pretty much a best-case scenario. (Also notice how tax revenue dropped in the Great Recession. That will become important later.)

By the way, for this chart we treat Social Security and Medicare as if they were not separately funded. Payroll taxes are included in the revenue line and benefit payments are in the blue mandatory spending area. I think that is closer to reality, since taxpayers are liable for them regardless.

Under these projections, total federal debt will rise to $25 trillion sometime in 2021. If there is a new president, he or she will not have enough time to change that. Total debt by the end of the decade will rise to the mid-$30-trillion range. Note that these projections do not include off-budget spending (more on that later) which is significant.

The CBO also assumes the bond market can and will absorb almost $35 trillion worth of US government debt. When combined with state and local debt it will easily exceed $35 trillion. (State and local debt is already over $3 trillion. It will certainly rise in the next 10 years.)

Ray, I think you would agree that at some point there will be another recession in the US. I think we would also agree it is somewhat of a mug’s game to predict the timing of a recession more than a few months in advance.

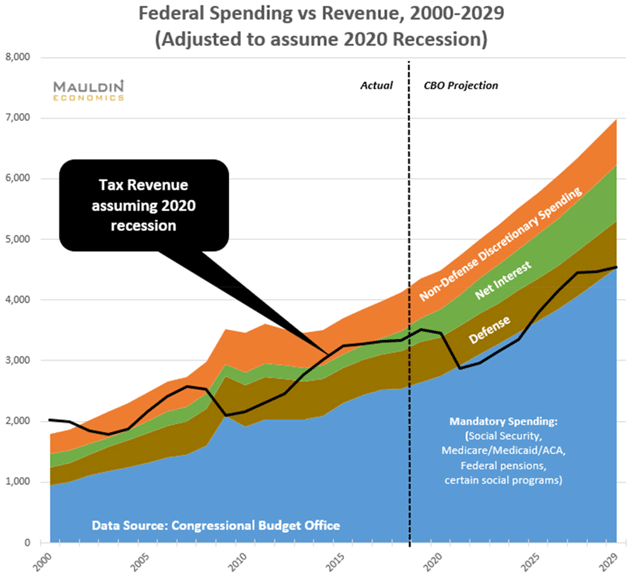

That being said, we should still ask what would happen to the deficits and debt if there were a recession. I asked Patrick to find the percentage change in tax revenues in the last recession (2008 and following) and the recovery thereafter. Using that historical data, the revenue line in the chart below assumes the same percentage revenue change following a hypothetical 2020 recession. (Note, recessions also raise spending due to increased unemployment insurance, welfare, and other economic backstops, but we ignore that in this chart.)

Possibly the next recession will not see revenues fall as much as the last one. Then again, it is also unrealistic not to expect an increase in expenses, so in my statistical dreamworld they will hopefully balance out. I’m sure we can look back in 2025 and see how close to the pin we actually were.

This first graph assumes a recession in 2020. Note that revenues fall below mandatory spending by the middle of the decade, then never get back above mandatory spending plus defense spending. Then by the end of the 2020s mandatory spending will again have risen to consume all tax revenue. And again, these deficits don’t include significant off-budget deficits.

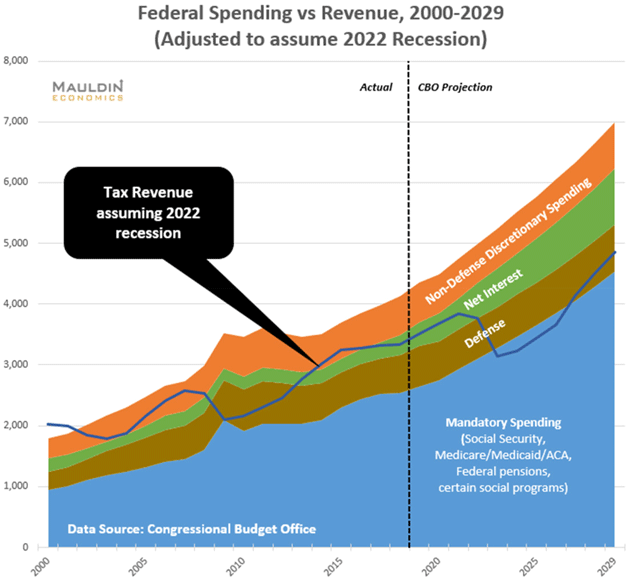

This next graph assumes recession in 2022 instead of 2020. The pattern is basically the same, except that the $2-trillion deficits don’t begin until 2023. Again, this uses actual CBO projections and reduces revenues by the same percentage they fell in 2008–2009, and recovered thereafter.

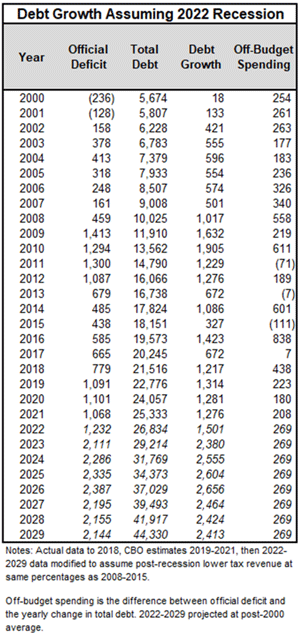

Finding a simple projection for off-budget deficits is extraordinarily difficult. When you begin to look at the actual numbers over the last 20 years, you can understand why. There can be a difference of as much as $950 billion from one year to the next. A lot of it has to do with accounting vagaries and statistical timing, which of course are hard to forecast years in advance.

That being said, there is a remarkable consistency about the average annual off-budget deficit. It has averaged around $269 billion a year since 2000. Since 2009 the average is $271 billion.

The following table looks at the actual growth of the US debt since 2000 and uses CBO projections for both on- and off-budget deficits through 2021. After 2021 we conservatively assume that the off-budget deficit will average $269 billion for the next eight years. We also assume, for the sake of mathematical interest, a recession in 2022. We did not project a tax increase at any point in the future, which would of course have an impact on future revenues and deficits. For those curious, a recession in 2020 would increase the total debt by more than $2 trillion in 2029.

Under these assumptions, annual deficits rise to over $2.5 trillion by 2024 assuming a 2022 recession. It will be hard for any administration to raise taxes after recession for at least a few years. And as we saw last week, even a 25% tax increase on the highest tenth of income earners in America would only produce about $250 billion. And that is not net and does not assume any behavioral change that reduces total taxable income of that top 10%.

Under our assumptions total federal debt will rise to over $44 trillion by 2029. The CBO forecast that does not include a recession has total debt rising to over $33 trillion. There is one line on page 16 of the report mentioned below which discloses that factoid. The rest of the report talks about government debt held by the public, as if debt held in the Social Security “lockbox” and other similar inter-government debt won’t be paid by the public as well.

Explaining off-budget deficits can be exhausting. Literally. But essentially, it is Congress appropriating funds from government agencies that are theoretically used for future expenses like pensions and healthcare, spending the money this year and replacing it with government bonds. Social Security obviously, but the US Post Office, all kinds of government pension funds, and all sorts of funds go into this budget legerdemain.

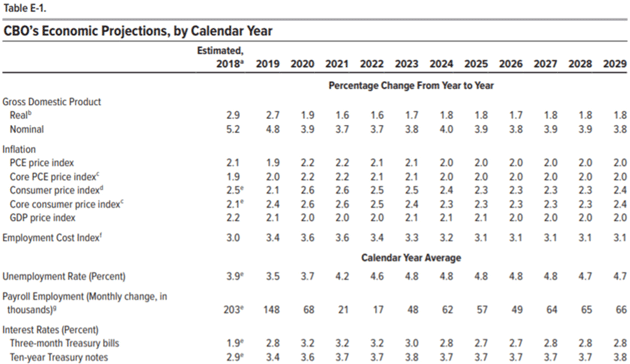

The CBO produces a remarkably detailed report on the budget and economic outlook through 2029. It is very clear in its assumptions. Let’s look at its GDP projections for the next 10 years: slightly under 2% average growth with 2% inflation and modestly increasing interest rates. (Page 147 at the link above)

Source: Congressional Budget Office

On page 126 you find that a 1/10 of 1% decrease in productivity could increase federal deficit spending by $307 billion over the next 10 years. Clearly productivity matters. Labor force growth has about half the effect of productivity growth. But both are significant.

The CBO projects US GDP will be in the $30-trillion range by 2029, again without a recession, which would no doubt shave a few trillion dollars off that number, but let’s go with it. Without a recession debt is projected to be about 105% (give or take) of GDP and with a recession it is closer to 150%. Shades of Italy or Greece.

Paul Krugman and many others would say I’m being unduly bearish and foolish to worry about deficits and national debt. “We” just want to wear our hair shirts and force austerity on everyone. The Italians are vocally resisting such austerity, as they saw what happened to Greece when the EU forced it to live within a budget. It could only be called a six-year+ depression. “Brutal” hardly describes it. Why would I wish such a turn of affairs on the US?

Maybe I’m just afraid of finding out the answer to “How much debt is too much debt?” We will know the answer only when the bond market rebels, and then it will be too late. Much too late.

Can the Fed intervene? Surely. But at what cost?

The problem is the data and research, by Lacy Hunt and others, shows a clear correlation between higher debt, lower GDP growth, and lower productivity. This will increase the deficit and debt in a vicious spiraling downward cycle.

It also increases the likelihood of QE4, 5, and ∞ into the future after the next recession, which will produce outcomes you (and I) are clearly unhappy with. With reasonable justification.

As for raising taxes to make up the difference, total income taxes in 2018 were less than $1.7 trillion. If you literally doubled taxes on the top 10%, you would only get an extra trillion dollars and still not come close to balancing the budget. Not to mention the recession such a tax increase would cause.

After a recession? It wouldn’t even close half the deficit gap with a 100% increase. And that’s before any increased spending. Some of the ideas run into the trillions of dollars over the next 10 years. Maybe that’s just a rounding error given the actual deficits, but these things do matter.

The cash government spends in excess of its tax revenue has to come from somewhere. If somehow it comes from the bond market (read US investors, as non-US investors in government bonds are increasingly scarce), that reduces the amount available for more productive endeavors, and thus reduces growth. If it comes from QE it increases distortions and misallocations in the market and, as you pointed out, increases wealth disparity. I am not exactly certain what MP3 would mean, but I look forward to learning.

Or…

Or we could completely (and somewhat radically) restructure the entire tax code along with getting expenditures under control (and maybe even reduced in some areas) and over three or four years come to a balanced budget. Let’s speculate about what that might look like…

(To be continued next week…)

As you read this, Shane and I are in Boston for Steve Cucchiaro and his beautiful bride Jama’s wedding Saturday night. The next day I meet with my business partners in Mauldin Economics (Olivier Garret and Ed D’Agostino). Monday morning I fly to New York where I am with CMG partner Steve Blumenthal, visit with Art Cashin, attend more meetings, have a CNBC shoot Tuesday afternoon for the Closing Bell, have dinner with accredited investor clients and prospects on Tuesday, and more meetings Wednesday before flying back to Puerto Rico on Thursday, July 4.

Early August sees me in New York for a few days before the annual economic fishing event, Camp Kotok. Then maybe another day in New York before I meet Shane in Montana and spend a few days with my close friend Darrell Cain on Flathead Lake.

Shane and I celebrated her birthday and our wedding anniversary yesterday. It was quite glorious. We are really enjoying living in Puerto Rico, much more than I expected. I don’t think I can get Shane to move with dynamite. And if she’s not moving, I’m certainly not.

On a final thought, my editor Patrick Watson and I spent hours this week going back and forth over these deficit and spending numbers, along with my other thoughts you will read next week. As we talked, I asked him what he thought about my outlines. “John, you are being way too optimistic!” If $44 trillion is optimistic…

And with that I will hit the send button. You have a great week and I hope you get to be with some friends and family. All the best!

Your worried about deficits and debt analyst,

| John Mauldin

Chairman, Mauldin Economics |