-- Published: Monday, 16 December 2019 | Print | Disqus

French Connection

Suppressed Competition

Do Hard Things

Reach Out & Listen

VIP Access

Christmas in Puerto Rico, Pat Cox, and More

We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.

—John F. Kennedy, 1962

When you write for a wide audience, no matter what you say, or how carefully you say it, some people will misunderstand.

Sometimes it’s amusing. Reading through my feedback (and I do read all of it), I get called both heartless capitalist and bleeding-heart socialist… in reaction to the same article.

In fact, I’m neither. I am a capitalist, and proudly so. I believe free markets are the best way to bring maximum prosperity and peace for everyone. But I’m not heartless, nor do I think markets are perfect. Even the best medicines can have serious side effects. That is doubly so when you aren’t taking the medicine correctly.

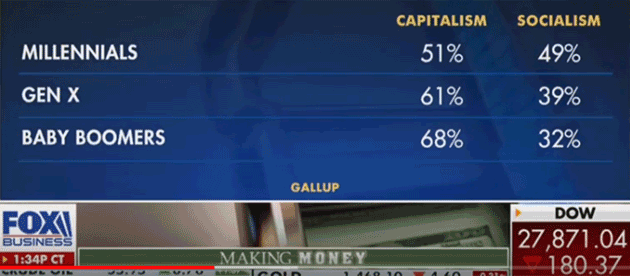

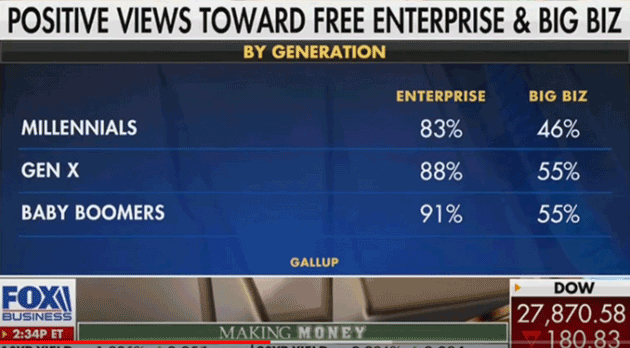

With a nod to Inigo Montoya of The Princess Bride, I don’t think the word capitalism means what we think it means, at least those of us of a certain age. Look at the two charts below from an interview Charles Payne did with David Bahnsen on Fox Business a few weeks ago. Notice that 49% of Millennials favored socialism. But if you ask if they favor “big business” or “free enterprise,” the numbers change significantly.

Source: Fox Business

In the future, I intend to substitute “free market” for capitalism where possible.

Much of the reaction to last week’s Inflationary Angst letter boiled down to, “Get government out of the way and the free market will work.” Others said the opposite: Government must help people even more than it already does. I wish it were that easy. Neither of those options are what we need, and today I will explain why.

In my last letter I discussed how standard inflation measures don’t capture the higher living costs most people face, particularly for the very things needed to better themselves. It’s hard to start a business if you have health problems and can’t afford treatment. That college degree that would let you get a promotion is increasingly expensive. And you can’t move to the big cities where better jobs are available if housing costs are out of reach.

We can point to many reasons those are expensive. It’s no coincidence that healthcare, housing, and education are all well-protected from foreign competition. They’re also subject to many regulations that raise costs. Other factors are also at work. Few of them are things the government can change by fiat.

As much as people like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren might wish, European-style taxation and government benefits aren’t the answer. They aren’t even working in Europe. We see this in France, where street protests are becoming a way of life.

Here’s an enlightening snippet from a recent Bret Stephens column in The New York Times.

Successive French administrations of both the left and right have been trying to reform this and other aspects of the country’s statist economy for decades, with limited results. Social benefits, once given, are hard to pare, much less withdraw. Hence the frequent strikes: Since 1789, French governments have been acutely sensitive to mass protests, and too often have capitulated to them.

Hence also France’s perennial economic crisis.

The country’s unemployment rate has not fallen below 7 percent since 1983 and is now at 8.6 percent. Long-term unemployment exceeds 40 percent, compared with 13.3 percent in the US. The country’s annual growth rate has barely exceeded an average of 1 percent per year since the 21st century began. It’s expected to come in at 1.3 percent for this year.

As of last year, the median monthly take-home pay was just $1,930, meaning half of all French workers make even less. It’s why the country erupted in protest when Macron proposed raising fuel taxes a few cents per liter.

How much of this is a matter of the French making different, arguably better, choices when it comes to balancing work and leisure? Surely some. And how much of it is made up for by quality public services, strong worker protections, and fewer economic inequalities? Some, too.

Then again, the health service that used to be the toast of Francophiles is overwhelmed, understaffed, and “on the brink of collapse,” according to a report in The Guardian. French universities, while cheap, are overcrowded, underfunded, and notoriously mediocre: “Too easy to get in and too easy to get out,” as one local observer put it. French workers exercise their right to strike roughly seven times more frequently than German workers do, and 125 times more than Swiss ones.

As for income inequality, France is certainly much less unequal than the US. But France’s top 1 percent still held 22 percent of the country’s wealth at the beginning of 2018. That was despite a draconian effort by the previous Socialist government to impose a super-tax on high earners. It raised scant revenue while accelerating the exodus of the rich. Like many European attempts at imposing a wealth tax, it was quickly repealed.

All of this should stand as a stark warning to Democrats. France has the highest overall tax take among OECD countries (46.9 percent of GDP), the highest rate of government spending, (56.38 percent of GDP), the highest rate of safety-net spending, and the third-highest rate of pension spending.

Whatever else all this taxing and spending might be doing, it’s clearly not creating jobs or prosperity.

US median per capita monthly income is about $2,600, considerably more than France. Very few people in the US would be willing to have their incomes cut by 40% in order to live in the French utopia. But if you are going to raise US taxes in the US (you have to combine state and local with federal) the money will have to come from the entire food chain.

Capitalism, at least the free market version, can’t work without competition. It motivates producers to offer the best products at the lowest prices, and lets consumers choose whatever best fits their needs. Yet instead of encouraging and protecting competition, the US government increasingly suppresses it.

Last February I wrote about a then-new book, The Myth of Capitalism, by old friend Jonathan Tepper and Denise Hearn. They aren’t leftists at all. They respect classical capitalism and want it to work better than it is.

Here’s a quick snippet from the book.

"Free to Choose" sounds great. Yet Americans are not free to choose.

In industry after industry, they can only purchase from local monopolies or oligopolies that can tacitly collude. The US now has many industries with only three or four competitors controlling entire markets. Since the early 1980s, market concentration has increased severely. We’ve already described the airline industry. Here are other examples:

- Two corporations control 90 percent of the beer Americans drink.

- Five banks control about half of the nation’s banking assets.

- Many states have health insurance markets where the top two insurers have an 80 percent to 90 percent market share. For example, in Alabama one company, Blue Cross Blue Shield, has an 84 percent market share and in Hawaii it has 65 percent market share.

- When it comes to high-speed internet access, almost all markets are local monopolies; over 75 percent of households have no choice with only one provider.

- Four players control the entire US beef market and have carved up the country.

- After two mergers this year, three companies will control 70 percent of the world’s pesticide market and 80 percent of the US corn-seed market. The list of industries with dominant players is endless. It gets even worse when you look at the world of technology. Laws are outdated to deal with the extreme winner-takes-all dynamics online. Google completely dominates internet searches with an almost 90 percent market share. Facebook has an almost 80 percent share of social networks. Both have a duopoly in advertising with no credible competition or regulation.

Amazon is crushing retailers and faces conflicts of interest as both the dominant e-commerce seller and the leading online platform for third-party sellers. It can determine what products can and cannot sell on its platform, and it competes with any customer that encounters success.

Apple’s iPhone and Google’s Android completely control the mobile app market in a duopoly, and they determine whether businesses can reach their customers and on what terms. Existing laws were not even written with digital platforms in mind.

So far, these platforms appear to be benign dictators, but they are dictators nonetheless.

It was not always like this. Without almost any public debate, industries have now become much more concentrated than they were 30 and even 40 years ago. As economist Gustavo Grullon has noted, the “nature of US product markets has undergone a structural shift that has weakened competition.”

The federal government has done little to prevent this concentration, and in fact has done much to encourage it. Broken markets create broken politics. Economic and political power is becoming concentrated in the hands of distant monopolists.

The stronger companies become, the greater their stranglehold on regulators and legislators becomes via the political process. This is not the essence of capitalism.

True, nothing stops investors from creating competition for Facebook, Google, and Amazon. Well, nothing except that it would take tens of billions of dollars in a very high-risk venture.

Many of today’s large corporations would collapse if we had actually free markets—for instance, insurance companies protected from out-of-state competition. So in one sense, it’s true that we need government out of the way. But we need to remove not just regulations, but also the various subsidies and favors as well.

Sadly, I have a hard time getting conservative friends to see this. They think that resisting left-wing policies is enough. But we have to do more than stop bad policies. We have to offer something better than “let nature take its course.”

Tom B., one of my regular correspondents, is a good example. Reacting to last week’s letter, he sent the France article quoted above, and this note.

Wow, John… I gotta admit, I don’t agree with your 80% figure for suffering Americans, maybe it’s 20% or less. Many get healthcare from employers or government, the number getting unsubsidized Obamacare is less than 5M, I think.

When in our history have people not had to relocate for economic opportunity? I’m from a fading steel town in AL, and made my way to the Silicon Valley. Didn’t our ancestors endure far worse hardship to come here? You might also think how government intervention in the three big sectors of housing, education, and healthcare has driven up prices, and that more than the Fed is to blame for inflation.

Europe has far worse economies than ours, yet little problem with drug addiction. These deaths of despair are a unique phenomenon to us that I don’t begin to understand. I do not believe the answers lie in economics, most of these people have marginalized themselves from the economy in ways that are hard to reverse. BTW worker laments are common these days, as they always have been…

When haven’t we seen this? Remember “The Jungle” by Upton Sinclair? Haven’t auto assembly lines always required workers to go at a fast pace?

Tom thinks only 20% of Americans are suffering the kind of angst I described. I think it’s more, and to be fair I probably should use Ray Dalio’s 60% line, but let’s go with Tom’s number. It still means some 66 million people are, in his words, “marginalized from the economy in ways that are hard to reverse.”

Hard to reverse? Maybe so, but that’s no reason not to try.

Tom is right: getting everyone connected to the economy and sharing in our prosperity is a big challenge. So was sending men to the moon. When JFK called on Americans to set that goal, he said we do such things because they are hard. The nation went to work and, a remarkably short time later, Neil Armstrong took that one small step, representing us all and indeed, all mankind.

We’re Americans. We can do hard things.

As for those worker laments, maybe their growing prevalence says something important. I think one of our greatest achievements is to have eliminated the kind of working conditions depicted in The Jungle. A capitalism that lets such horrors return, or anything remotely like them, isn’t working like it should.

But humanitarian concerns aside, abandoning millions of people to the wolves probably won’t end well for the top tier. Historically, regimes survived by giving the masses bread and circuses, which worked for a time but had limits. Marie Antoinette learned the hard way. We have limits now, too, and they’re getting closer.

Whatever happens in the 2020 elections, governing such a bitterly polarized country will be tough. Which means the economic problems I’ve described will fester and probably get worse. That leads nowhere good.

The only way out of this, the only way to preserve what we have and get through the 2020s, is for people to set aside their tribal loyalties, work together, and find solutions. That means none of us will get everything we want. We’ll have to compromise in unpleasant and distressing ways. But the alternatives will be even less pleasant and more distressing.

One alternative, increasingly discussed by serious people, is for the US to simply break up. Let the blue states do their thing and the red states do theirs. The problem: no state is purely blue or red. All have substantial minorities loyal to the other tribe. So it would be messy, to say the least.

We don’t have to put ourselves through that trauma. As I said above, we can do hard things when we have to. Recently I ran across this story about 1970s Durham, North Carolina. Courts had just ordered the city to integrate its schools. Violence was a real possibility.

Two local activists who to that point had basically hated each other were pressured into leading a series of public meetings to ease the process. Ann Atwater was a single, poor black parent and C.P. Ellis led the local Ku Klux Klan. Neither wanted anything to do with the other, but both saw what had to be done.

To plan their ordeal, they met and began by asking questions, answering with reasons, and listening to each other. Atwater asked Ellis why he opposed integration. He replied that mainly he wanted his children to get a good education, but integration would ruin their schools. Atwater was probably tempted to scream at him, call him a racist, and walk off in a huff. But she didn’t. Instead, she listened and said that she also wanted his children—as well as hers—to get a good education. Then Ellis asked Atwater why she worked so hard to improve housing for blacks. She replied that she wanted her friends to have better homes and better lives. He wanted the same for his friends.

When each listened to the other’s reasons, they realized that they shared the same basic values. Both loved their children and wanted decent lives for their communities. As Ellis later put it: ‘I used to think that Ann Atwater was the meanest black woman I’d ever seen in my life… But, you know, her and I got together one day for an hour or two and talked. And she is trying to help her people like I’m trying to help my people.’ After realizing their common ground, they were able to work together to integrate Durham schools peacefully. In large part, they succeeded.

That may seem out of reach now. But if you, like me, remember the segregated South, you know how deep those attitudes were. Somehow people got past them, though not perfectly or easily.

Our greatest enemy isn’t “the other side,” but the feeling on both sides that reconciliation is impossible. I reject that thought. I believe we can get through this period together. Yes, it will be hard. But that’s why we must do it: because it is hard.

My great fear is we’ll have to go through the economic equivalent of World War II before we finally compromise. It may take a new low point to make us bite the bullet—hopefully not a literal one.

As I’ve said in previous letters, there are things we can do to avoid that, but both sides will have to give up some of their ideological “no compromise” positions. They’re going to do that anyway after the Great Reset, from a decidedly lower base. Better to make the hard decisions today.

One of my favorite Mauldin Economics services, VIP, has just reopened its doors to new members. When you become a VIP club member, you get all seven of our publications (plus the VIP Week in Review summary) at a special member-only discount.

I invite you to dive into our “full-spectrum” experience. It’s like nothing you’ve ever seen. The Mauldin Economics editors are masters in their fields. And as a VIP club member, you can get all their diligent research at a steep, practically unheard-of 64–75% discount.

So please consider this limited-time offer (VIP only opens to new members once or twice a year) and click here for the details.

I’m finishing this letter a little early (Thursday afternoon) because tonight is a very large community Christmas party. Later tonight Pat and Cheryl Cox fly in. We will spend the next three days working on parts of my book. I’m really getting tired of talking about this book and looking forward to finishing it.

We are also deep in planning for the upcoming Strategic Investment Conference which will be in Scottsdale, May 11–14. I really think this will be the best and most unique conference we’ve ever done. Mark your calendars.

With that I will hit the send button. I’m looking forward to Christmas in Dorado Beach. It has been one year since we moved here, and while I admit that taxes were a big reason we came, Shane and I now realize we should have come for the lifestyle and oh yes, the tax situation is better.

Your as busy as ever but more relaxed analyst,

| John Mauldin

Co-Founder, Mauldin Economics |