-- Published: Tuesday, 18 February 2020 | Print | Disqus

GDP Genesis

We Need a Pleasure Measure

Flawed Data Dependence

My 2020 Forecast and the Coronavirus

SIC Registration Is Open

The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of [GDP].”

—Simon Kuznets (who developed GDP), 1934

At the risk of restating the obvious, production should result in a product the producer can recognize. That’s the case even for intangible products. Artists know their songs even if hearing a pirate copy.

This also applies to a country’s aggregate production, i.e., Gross Domestic Product. Of course, we can’t expect the government to count every single widget we make. Nor should we want them to; the collection process would be pretty intrusive. But they should be able to make a reasonably close estimate.

Yet we have no such estimate. As I explained last week, we use GDP because we have nothing better, but it misses a lot. Business, government, and especially Federal Reserve policymakers look at GDP when they make important decisions. Is it any wonder that flawed data leads to flawed policies?

Today we’ll extend the GDP discussion, looking at where these numbers originate, what they miss, and what the Fed in particular does with them. As you’ll see, we need better data… but it’s not at all clear Fed officials would use such data correctly, even if they had it.

GDP Genesis

GDP comes from the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis. Compiling it is a giant, difficult, never-ending task, one the BEA staff takes seriously. From time to time, we hear stories about political interference, but I think that unlikely. Too many people are involved to keep any such efforts secret.

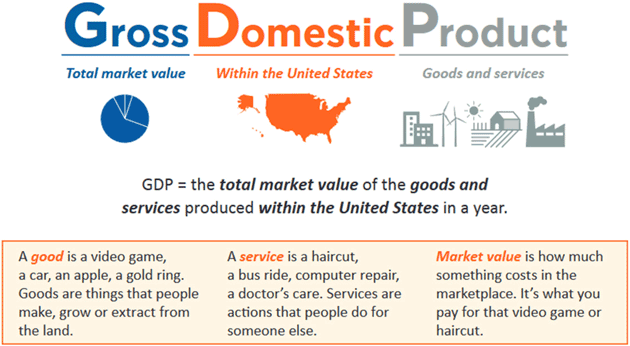

The BEA has a handy, colorful, two-page sheet on its website that explains today’s GDP in big letters. Here is how they define it.

Source: BEA

As they explain it, GDP is the total market value of the goods and services produced within the US each year. Seem simple? It’s not. Those seemingly simple terms hide enormous complexity.

Several centuries ago there was a big debate about what “production” meant. The classical economists had little concept of manufacturing. To them, it was all about land, and mainly agriculture. This “physiocrat” philosophy originated in France, assuming wealth derived solely from land and agriculture.

The physiocrats thought merchants and manufacturers simply shuffled the fruits of agriculture and contributed little to the overall economy. The First Industrial Revolution pretty much put that theory to rest.

That worked fine for a few centuries until we started producing ephemeral yet valuable things like social networks, for which consumers paid with their attention instead of their money. Unsurprisingly, with the advent of the information and digital society, there is yet another debate on what is the measure of true value and wealth. More on that later.

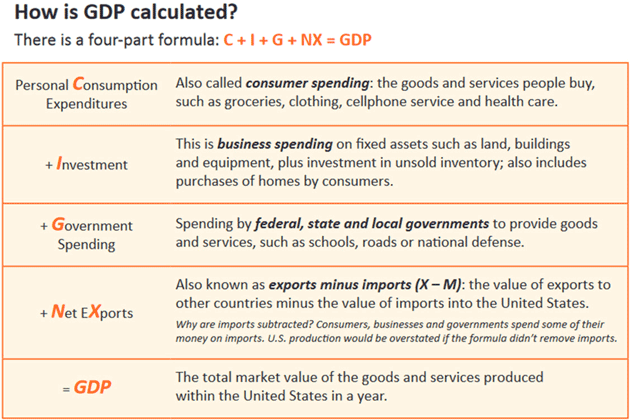

BEA wrestles with thousands of such questions. Some are harder to quantify than others. The answers go into the master formula, C+I+G+NX = GDP. Or, as BEA explains it…

Source: BEA

That first category, PCE, is both a component of GDP and the Fed’s preferred inflation measure. They have been trying (and failing) to get its annual change up to 2%.

Business investment has also been lagging, in part because PCE growth has not been enough to require new production capacity.

Government spending has done the opposite of lag, instead growing at a rapid and accelerating pace. And as I noted last week, there was considerable debate about whether including government spending was simply double counting, as at one time back in the dark ages government spending correlated directly with taxation. Some argue, not unreasonably, that government spending is actually a drag on total GDP when properly measured.

Net exports is another way of looking at the “trade deficit.” Our imported goods subtract from GDP but, if they cost less than domestic alternatives, can give consumers and businesses more money to spend, which boosts GDP. So exports help but imports don’t necessarily hurt.

This formula made at least some sense when they began using it in the 1940s. Now, less so. But if you are a Federal Reserve governor, charged with generating economic growth, those are the knobs you can turn. Ditto if you are a president or member of Congress. Most everything they all do, from tax and trade policy to interest rates to “stimulus” spending, aims to change one or more of these GDP inputs.

As BEA’s graphic shows, GDP is the market value of the goods and services we produce. That’s fine, as far as it goes. Usually it suffices, but it presumes a) markets exist and b) they can identify a fair and accurate value. That is increasingly not so.

For instance, what is the market value of Google maps, Facebook, or Wikipedia? All are free to consumers. They have no market value, yet they’re clearly valuable.

This is a big problem for GDP. Here are MIT economists Erik Brynjolfsson and Avinash Collis, writing in Harvard Business Review last year.

GDP is often used as a proxy for how the economy is doing. To look at it, you would think it is a relatively precise number that signals every quarter whether the economy is growing or shrinking. If it goes out to two decimal points, how can it not be precise? (Note sarcasm.) However, GDP captures only the monetary value of all final goods produced in the economy. Because it measures only how much we pay for things, not how much we benefit, consumer’s economic well-being may not be correlated with GDP. In fact, it sometimes falls when GDP goes up, and vice versa. And that is especially true for the individual, as we will see.

The good news is that economics does provide a way, at least in theory, to measure consumer well-being. That measure is called consumer surplus, which is the difference between the maximum a consumer would be willing to pay for a good or service and its price. If you would have spent as much as $100 for a shirt but paid only $40, then you have a $60 consumer surplus.

To understand why GDP can be a misleading proxy for economic well-being, consider Encyclopedia Britannica and Wikipedia. Britannica used to cost several thousand dollars, meaning its customers considered it to be worth at least that amount. Wikipedia, a free service supported by donations (which I encourage), has far more articles, at comparable quality, than Britannica ever did. Measured by consumer spending, the industry is shrinking (the print encyclopedia went out of business in 2012 as consumers abandoned it). But measured by benefits, consumers have never been better off.

That all makes sense, but what can we do about it? Brynjolfsson et al. did a series of experiments in which they asked people how much money they would want in order to give up Facebook, or Wikipedia, or other hard-to-measure “free” services. The answers varied but they were able to calculate averages, which were surprisingly high. US consumers would want about $500 annually to give up Facebook—quite a bit more than Facebook generates in ad revenue.

That means Facebook, alone, would have added 0.11 percentage points per year to US GDP from 2004 through 2017. Add the consumer surplus for other free services and we could be undercounting growth by a full percentage point annually.

That doesn’t mean Facebook or Google are our economic saviors. The point is that our prime economic growth measure, GDP, is missing an enormous amount of “value” simply because it doesn’t fit the formula. This has consequences.

Central bankers, in the US and elsewhere, are not oblivious to these measurement problems. They know their data is flawed, even as they call their policies “data dependent.”

Jerome Powell discussed these same issues in a speech last October 7 called Data-Dependent Monetary Policy in an Evolving Economy. (That was the same speech, you may recall, in which he casually mentioned the Fed would begin injecting new reserves to deal with the then-unfolding repo crisis. I said at the time it didn’t inspire confidence, and indeed they are still pumping now, months later.)

Powell argued the Fed can do its job even with imperfect data. He described some of the challenges I did above, even giving Brynjolfsson a couple of footnotes.

The advance of technology has long presented measurement challenges. In 1987, Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow quipped that "you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics." In the second half of the 1990s, this measurement puzzle was at the heart of monetary policymaking.

Chairman Alan Greenspan famously argued that the United States was experiencing the dawn of a new economy, and that potential and actual output were likely understated in official statistics. Where others saw capacity constraints and incipient inflation, Greenspan saw a productivity boom that would leave room for very low unemployment without inflation pressures.

In light of the uncertainty it faced, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) judged that the appropriate risk‑management approach called for refraining from interest rate increases unless and until there were clearer signs of rising inflation. Under this policy, unemployment fell near record lows without rising inflation, and later revisions to GDP measurement showed appreciably faster productivity growth.

This episode illustrates a key challenge to making data-dependent policy in real time: Good decisions require good data, but the data in hand are seldom as good as we would like. Sound decision making therefore requires the application of good judgment and a healthy dose of risk management.

Fair enough. To paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld, you go to the FOMC with the data you have, not the data you want. But Powell doesn’t seem to get this idea of “market pricing” when the market is interest rates. He said this:

The Federal Reserve sets two overnight interest rates: the interest rate paid on banks' reserve balances and the rate on our reverse repurchase agreements. We use these two administered rates to keep a market-determined rate, the federal funds rate, within a target range set by the FOMC.

Think about his last sentence. Federal funds is a “market-determined” rate that must stay in the range the FOMC decrees. That is nonsense. If fed funds has to stay within a range Powell’s committee sets, it isn’t market-determined. It is FOMC-determined with a little bit of wiggle room, the amount of which is also FOMC-determined. And the FOMC determines it using data Powell himself says is “seldom as good as we would like.”

See the problem?

Here’s the real question. If they did have good data, would Powell and other central bankers use it? Count me dubious. They like their flexibility too much. They proclaim themselves data-dependent, then use the data’s flaws to justify doing whatever they really want.

And that data has an agenda. As an example, it looks like Judy Shelton is running into trouble getting confirmed for the Fed. Mainstream economists don’t like her, perhaps because she says things like this (from Friday’s WSJ):

The increasing financialization of gross domestic product is unhealthy because the growing size and profitability of the finance sector comes at the expense of the rest of the economy and increases income inequality… The kind of economic growth that increases living standards across all income levels occurs under conditions of monetary and financial stability.

Yet another way that the Fed “looking at the data” distorts the economy and GDP. Because the data they look at is helping Wall Street, not those who are struggling day to day. Here’s Annie Lowrey writing in The Atlantic.

Viewing the economy through a cost-of-living paradigm helps explain why roughly two in five American adults would struggle to come up with $400 in an emergency so many years after the Great Recession ended. It helps explain why one in five adults is unable to pay the current month’s bills in full. It demonstrates why a surprise furnace-repair bill, parking ticket, court fee, or medical expense remains ruinous for so many American families, despite all the wealth this country has generated. Fully one in three households is classified as “financially fragile.”

Yet the Fed thinks we need more inflation.

The Federal Reserve makes national monetary policy. Just as national average inflation probably doesn’t reflect your personal situation, the nation’s average GDP doesn’t reflect individual situations. I have written about this in the past, especially in my exchanges with Ray Dalio. Viewed through income and affordability lenses, there are multiple Americas with different needs. Different companies and regions would probably prefer a tad bit more nuance in interest rate policy.

GDP, or any other national average, simply can’t capture all the variation in a country as large as the US. That greatly reduces its analytical value. Here’s Guggenheim CIO Scott Minerd on the problem of measuring economic growth.

From 1961 through 1966, average annual US Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew about 5 percent, while the unemployment rate averaged 4.8 percent, and inflation was under 2 percent. Knowing just these data points, you would never get a sense of the economic and social inequities that led to 1967’s Long Hot Summer of race riots.

In 2006 and 2007 most investors and policymakers missed the signs that the engine of economic growth associated with rapid house price appreciation would prove to be the source of global financial disaster.

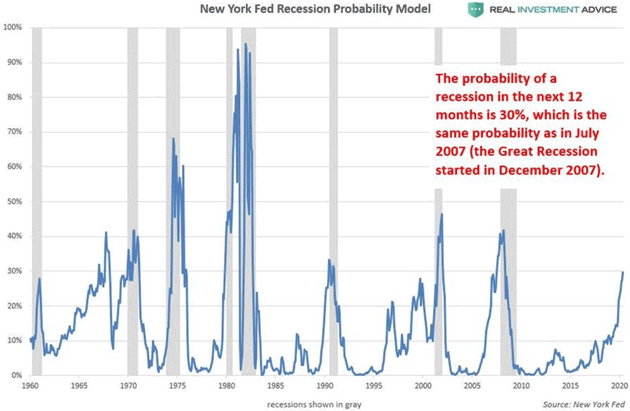

Economic historians will recognize 1966 as the beginning of a 16-year secular bear market. Stock benchmarks didn’t recover until 1982 and on an inflation-adjusted basis not until 1992. Note that in the chart below from my friends at Real Investment Advice there were four recessions during that period. Now we have just gone through the first decade in US history without a recession. They also note the New York Fed recession probability is getting uncomfortably high.

Source: Real Investment Advice

I have said repeatedly for the last three or four years that I don’t expect recession within 12 months (you can’t really see much further than that in the data) barring some “exogenous shock” from outside the US. I usually cite Europe and China as the main possibilities.

My 2020 forecast was for slower growth but no recession. But now we may be getting that exogenous shock via China’s coronavirus. Good friend and fishing buddy David Kotok of Cumberland Advisors has long been a keen epidemic watcher. It’s kind of his personal thing. He was all over SARS, Ebola, Zika and others. Now he says what we all know: China is lying about the data.

China cannot be trusted on any statistic. We have suspected that for years, with plenty of evidence. Now we have absolute proof.

It is literally impossible for epidemiologists, even without government pressure, to accurately know the number of deaths caused by the virus until after the fact. They can make guesses, but they do it without good data. In this case, it seems they were making politically pressured lowball guesses and now are trying to catch up.

The best bet is to ignore the statistics and watch what the Chinese government does. From private sources, I have read quite chilling accounts of wartime-like policies—absolute lockdowns. My friend Dr. Mike Roizen says that’s the right thing to do. This virus is not SARS. It is transmittable well before you have symptoms, and there is now very credible evidence the virus can survive up to 12 days outside the body—say on a hospital table or in an apartment building.

The expectations that factories will reopen soon may not be met. And while the deaths are truly tragic, the coronavirus is clearly going to have an economic impact, too.

My favorite China bull now believes it probable China GDP will drop significantly this quarter. Note, 15% of US foreign trade is with China. Europe and others are also being impacted, which will affect our exports to them.

Please understand, I am not calling for a recession at this time. But the potential for an exogenous shock is higher now than at any time in the last 10 years. Hopefully, modern medicine will come up with a vaccine quickly. There is reason to be hopeful on that front—possible vaccines are already in animal trials in both the US and China. But the economic impact won’t wait.

We should also understand something else about the recovery. It’s tough to administer stimulus policies to areas that are in military lockdown. But the moment this virus is under control, China will likely go into the greatest stimulus campaign of the century. I know that’s saying a lot. It will impact global markets. It won’t surprise me to see the Fed proactively cut rates and for the ECB and other central banks to inject even more liquidity. As they say, stay tuned…

We’ve just seen how complex the concept of GDP is. And it’s not the only one: Nearly everything in the realm of economics and finance is complex (and often complicated, which is not the same thing). That’s why I read so much—understanding how all the threads of the tapestry fit together is not an easy task.

Thankfully, I have friends and colleagues to help me and my readers out. And one of the greatest concentrations of knowledge in our business is at our annual Strategic Investment Conference, May 11–14. I’ve never seen anyone attend who wasn’t impressed with the valuable information handed out by the bucketful.

If you’ve never attended an SIC, you simply have to. It’s an experience like no other. If you have attended before, you’ll be pleasantly surprised—because this year, at the request of our “SIC regulars,” we limited attendance to only 450 people. That gives you more one-on-one time with the Mauldin Economics team and the faculty. It also let us pick a smaller, more high-end venue for our event: the gorgeous Phoenician resort in Scottsdale, AZ.

Speaking of the faculty, we have secured two famous billionaires for our blue-ribbon lineup. The first is keynote speaker Sam Zell, chairman of Equity Group Investments and five other NYSE-listed companies. He founded and chaired the largest office REIT, which was sold for $39 billion in 2007. He also introduced the first Brazilian and Mexican real estate companies to the NYSE. He is listed on Forbes’ “100 Greatest Living Business Minds” together with names like Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and Jeff Bezos.

The other headliner is Leon Cooperman, a man with more business awards than grains of sand on our Puerto Rican beaches. In 1991, Leon retired as chairman and CEO of Goldman Sachs Asset Management to launch Omega Advisors, which he ran for 27 years before turning it into a family office.

That’s just a small glimpse of what you can expect at this year’s SIC, and I can’t wait to greet you there in person. You can see the rest of the lineup for what is going to be the best SIC ever at the website. But hurry—more than half of the 450 available seats are already gone. Get all the details and register here.

And with that I will hit the send button. I’m not going to New York, electing to stay home and write.

Your watching for exogenous shocks analyst,

| John Mauldin

Co-Founder, Mauldin Economics |

P.S. Want even more great analysis from my worldwide network? With Over My Shoulder you'll see some of the exclusive economic research that goes into my letters. Click here to learn more.

READ IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES HERE.

YOUR USE OF THESE MATERIALS IS SUBJECT TO THE TERMS OF THESE DISCLOSURES.

| Digg This Article

-- Published: Tuesday, 18 February 2020 | E-Mail | Print | Source: GoldSeek.com